Connecting with Culture

Our blog reflecting on weekly news, trends, innovation, and the arts...

Read

Jesus was famously called ‘a friend of sinners’ (Luke 7:34). He crossed every social divide. But today, many of us don’t have any close friends, be that inside the church, in our workplaces, or on our streets.

So, how do we practise friendship well, like Jesus and the early church did, as a witness to our lonely and fragmented world?

That’s the question this blog series explores. Over four articles, our contributors – Sheridan Voysey, Chloe Lynch, Corin Pilling, and Phil Knox – will have a conversation, responding to each other’s reflections as they ‘triple listen’ to wisdom from the Word of God, the world, and one another. The goal? To help our friendships flourish as whole-life disciples, wherever we are, whoever we are, and whatever we do.

The series also accompanies our Wisdom Lab: Friendship on the Frontline event, at which each of the authors will deliver a TED-style talk and bring together evidence-based insights and theological wisdom, making space for honest dialogue to inspire us to practise friendship in a more fruitful way.

In our first blog post, Sheridan Voysey – an author, broadcaster, and founder of FriendshipLab.org – helps us listen to our culture, so we can understand why these relationships are so hard to sustain. He leans into what makes for a real friendship. In the rest of the series, we’ll imagine what Scripture has to say, learn to create a healing response, and think about how to communicate the good news as a whole-life witness.

—

When the eighty-year-long Harvard Study of Adult Development concluded, researchers in this landmark health project arrived at a dramatic conclusion. The key to happiness and longevity, they found, wasn’t wealth, IQ, social class, or good genes – it was having strong relationships. This is both good and bad news for us today. Good, because wellbeing is available to us all, whatever our background. Bad, because many of us are struggling to enjoy the benefits friendship brings.

In this new Friendship on the Frontline series, we will explore this foundational relationship. Using LICC’s ‘Triple Listening’ framework for cultural engagement, this blog will help us listen to what’s happening to friendship in our lives and society, including the barriers against it, while subsequent blogs will help us imagine and create solutions to the problem. As we’ll see, we have much ground to gain – as Zara’s and Jez’s stories suggest.[1]

Zara is a 34-year-old architect living in Cambridge, where she moved five years ago. Lately, she’s been wondering if she should move somewhere else. For all her efforts, Zara hasn’t been able to make friends.

It’s not that Zara lacks social skills. She is friendly, listens well, laughs often, and has no problem initiating conversations or coffee dates. She chats with her childhood friend, Lori, on WhatsApp daily, and they’ve FaceTimed weekly since Lori moved to the US years ago. When Zara joined her architectural firm, she quickly made friends with fellow newbies Cath and Claire. Making friends has never been a problem for Zara, until now.

Zara’s workplace has changed significantly in recent years. Where once all 200 staff worked from the London office, the flexible arrangements maintained after the pandemic mean she now works mostly from home. She’s tried going into the office for company, but the few people present are virtually strangers. Cath has since taken a job in Kent; Claire has moved abroad. Things aren’t the same.

Faith is important to Zara. She’s part of a large church in Cambridge and values her Wednesday night home group dearly. But even there she feels disconnected. While her small group includes a healthy range of ages, she’s the only single 30+ woman there, and no one meets up outside of Wednesday nights. She reminisces about the bonds she had in her last church in Manchester, but those friends have also moved on.

There is one potential friend on Zara’s horizon – a 40-year-old mum of four who’s promised Zara a cycle ride when she has time. Zara’s trying. But right now she has questions:

Jez, 29, thanks God for the work he does. A keen cyclist from his youth, he bought a rundown bike store in his London borough six years ago, and it’s now thriving. With Jez selling or repairing bikes six days a week, and Sundays taken up with church and family, what free time he has he spends jogging, or relaxing with his wife Deb and a Netflix series.

Jez has heard plenty of sermons about the need to reach out to non-Christians, but beyond his family and customers, only really spends time with church folks – something he feels uneasy about. So, when Deb invited her colleague Sue and husband Daniel round one day, Jez was delighted to find that Daniel shared his love of cycling and running. In time they went for a ride together, with a pub stop along the way. Jez was spending time with a non-Christian, a missional motive fulfilled.

A nascent friendship has started between Jez and Daniel, and this has woken Jez to the fact that he rarely gets together with other men. In fact, he wonders if he’s had even one close friend since university. As his friendship with Daniel grows, questions emerge for him:

Zara and Jez are far from alone in trying to navigate friendship today. YouGov studies in 2019 and 2021 found that around 20% of Brits have no close friends, including 7% who have no friends at all. Just 12% of us have one close friend, and 51% of us admit we struggle to make new ones.

Such friendlessness figures are compounded by a steady stream of loneliness reports. According to the 2020–21 Community Life Survey, 6% of British adults are ‘always’ or ‘often’ lonely (that’s over 3 million people), and another 18% are ‘sometimes’ lonely.

All this adds up to what some on the other side of the pond have called a ‘friendship recession’, in what author Noreena Hertz has labelled our ‘lonely century’. We’ve never needed friends more, yet never found them harder to find. The question is, why?

The barriers to forming and maintaining friendship today are many. Long work hours, a lack of trust, rabid individualism, political polarisation, the isolating effects of smartphones and social media, and the decline of community institutions all play a role. I’ll highlight four forces that relate to Zara’s and Jez’s stories in particular, and likely to us all.

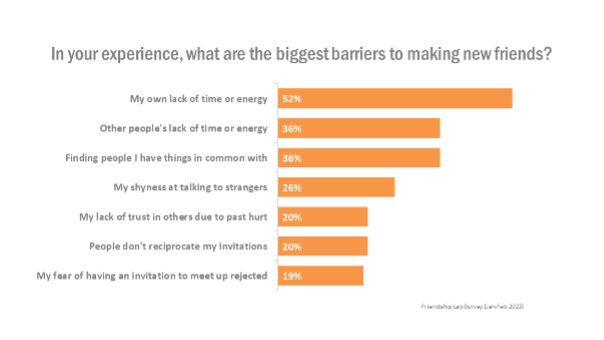

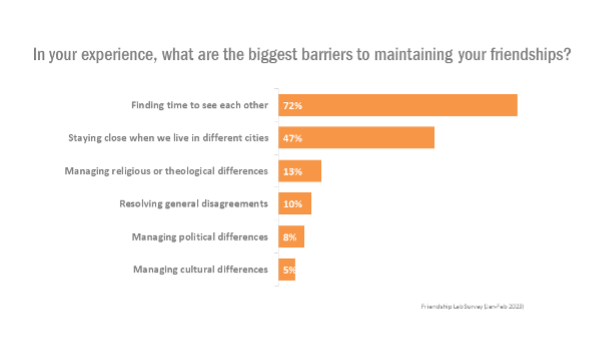

As Zara and Jez show, a lack of friends isn’t always a matter of lacking social skills. In fact, in most surveys, that fails to show as a factor at all. Instead, the most common barrier cited is busyness. With long work days, lengthy commutes, and a myriad of activities to ferry children to, there can be little time left for friends. We found this in our Friendship Lab survey of around 1000 people, in which participants said the greatest challenge to both making and maintaining friends was their own and others’ lack of time (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Jez’s experience will resonate with many: after work, family, and maybe church, there’s little time or energy left for anything else. Zara’s potential riding buddy will join her ‘when she has time’, and time constraints may be the reason her small group members don’t meet beyond Wednesdays. When it takes at least 50 hours of socialising for an acquaintance to become a casual friend alone, a lack of time is a significant barrier to friend-making.

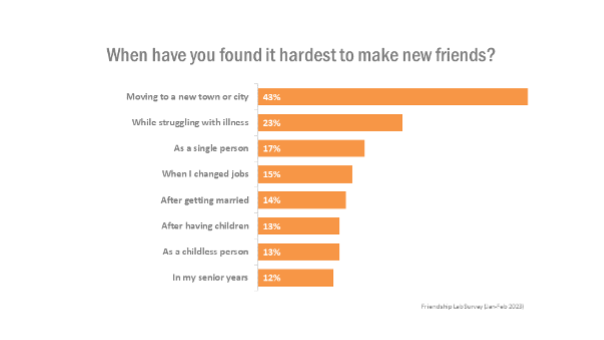

Zara moved to Cambridge from Manchester, leaving church friends behind who have themselves since moved on. Cath and Claire are now elsewhere, while Zara’s closest friend lives in the US. Welcome to our mobile age. Today we relocate for work opportunities or life-enhancing experiences – and this comes at a cost.

In our Friendship Lab survey, respondents reported finding it hardest to make friends after relocating to another town or city (Figure 3), while staying close to distant friends was the second major barrier to maintaining existing friendships (Figure 2).

Figure 3

While video technologies allow us to maintain friendships across distance like never before, friendship cannot live by WhatsApp alone. We need physical beings with us in the A&E ward, real shoulders to cry on. In his book Friendship, psychologist Robin Dunbar notes the ’30-minute rule’ – that we’re more likely to stay in touch with people in a 30-minute radius from where we live. Constant relocation breaks this law.

It’s also worth noting that Zara lives in Cambridge, a university city where population turnover can be high – though the award for this goes to Oxford, with a whopping 26% population turnover each year, due largely to its student population coming and going. Making a friend in such cities means the possibility that they may soon leave town.

There’s no doubt our social lives are still reeling from the Covid-19 pandemic. In the UK, around a third of us lost friendships during that surreal time, and a recent Pew Research poll found 35% of Americans now see socialising in-person and participating in large gatherings as less important.

We can’t lay all the blame for our friendship recession on the pandemic, however. According to the American Time Use Survey, the number of hours Americans spend with friends started declining back in 2014, dropping a massive 37% by 2019 alone. Westerners are spending more hours by ourselves than ever before, a trend one commentator linked to the fact that market penetration for smartphones crossed 50% in 2014.

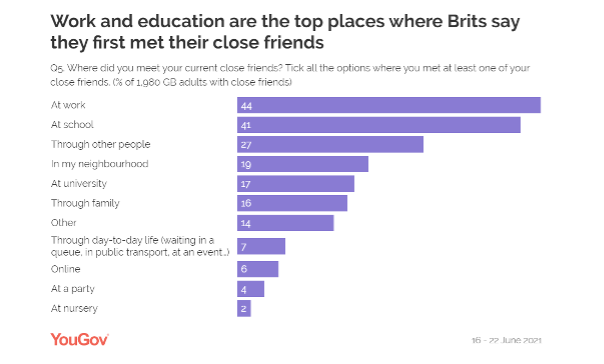

One of the more practical changes brought about by the pandemic relates to the workplace, with remote work arrangements seemingly here to stay. The wellbeing effects of this are mixed. While working from home saves us commuting time (reducing force 1, busyness), as Zara has found, it’s now harder to make or maintain workplace friendships. This is significant as the workplace is now the main place we adults make friends (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Our last force is one of vacuum rather than pressure, because undergirding all that’s been written above is the simple fact that friendship in our age has been ignored.

A quick look at our Spotify playlists will prove it, with any songs we find about friendship in them being mere drops in an ocean of love songs. We have sex education in schools, but little friendship education. We know the date of Valentine’s Day, but not International Friendship Day. In popular culture, education, and (until recently) science, our gaze has been on eros rather than philia. This was illustrated recently with the story of Jack and Zoe, whose ‘romance’ went viral after they met queuing to see the Queen lying in state. There was almost a country-wide sense of let down when it came to light that each already had partners and had only become friends.

We must face the fact too that friendship has been neglected in the church. As someone who has lived in five major cities across two countries, I thank God for the friend-making facility that is the local church. As one of the last remaining institutions to bring different people together, it has large- and small- group structures to enable connection, and with its emphasis on godliness (the fruit of the Spirit being the very virtues we need to make friendship work), it’s been a lifeline to me and millions more. But our gaze has also been elsewhere. We’ve produced books, courses, and launched whole ministries around marriage and parenting, but done next to nothing on friendship, something the Friendship Lab project will soon redress. When friendship has gotten a mention in churches, it’s often in the context as a means to another end, like evangelism.

Jez has heard plenty of sermons about reaching out to non-Christians. I wonder how many he’s heard about friendship. How many have you heard? This may be one reason Jez has neglected his own friendships and is now confused over his evangelistically-motivated relationship with Daniel. Friendship is a good in itself, not a means to some other end.

If the four forces weren’t enough to blow friendship off course, there’s also the confusion of language, for the word itself has been stretched to cover all manner of ill-fitting meanings. The internet is awash with sweet stories of ‘friendships’ between lonely grandmothers and toddlers, footballers and children in need, even divers and dolphins. Man’s ‘best friend’ is a dog, outreach to vulnerable people is called ‘befriending’, while a Facebook ‘friend’ can be someone we met at a colleague’s birthday party years ago and haven’t seen since. None of this resembles true friendship.

So, what is friendship? Let’s define the relationship and the personal qualities it entails.

Friendship is different to other relationships. Unlike marriage, no formal commitment binds it together. Unlike a business partnership, no legal contract defines its terms. Friendship is made and maintained on a voluntary basis. A workplace can’t force friendships between colleagues, and churches can’t force friendships between members (like cults do). Friends find something attractive in each other, preferring that person over others, and freely enter and stay in the relationship.

Friendship is also founded on equality. We mustn’t confuse a mentor for being our friend, or a counsellor, or our boss, or any other patron-client relationship we have. Such people can become our friends, of course, but only when the patron steps out of that role, even momentarily, to join us as equals. In our lonely century, this is a common source of confusion. A grandmother isn’t on an equal footing with a toddler, or an outreach worker with the person she serves.

And friendship is built on mutuality. I can be friend-ly towards you but unless you reciprocate, we won’t have a friend-ship. This has been a stumbling point for Christians who’ve wanted to live out sacrificial agape love. Aren’t we supposed to love others – even our enemies – even if they don’t reciprocate? Yes, indeed. But that doesn’t forbid enjoying mutual friendships too. If we subtly believe mutual friendship is indulgent or selfish, we’ll focus only on reaching and serving others, not making friends.

So, friendship is a voluntary, preferential relationship built on equality and mutuality. But as a practical definition, we can go further by describing not only the relationship, but the persons involved. At Friendship Lab, we work on a definition that I’ve taken from theorist William K. Rawlins and expanded:

‘A friend is someone I can talk to, depend on, grow with, and enjoy.’

Each element here is important. A friend is someone we can talk to about the little things and the large, from football scores to our doubts, hopes, and fears. They’re someone we can depend on to lend a hand when we move house, or be there at A&E when the accident happens. They help us grow into the people we’re meant to be, committed to our welfare, including our spiritual and eternal wellbeing. And they’re the ones we enjoy because of the laughter they bring, the insights they carry, or the sharp game of tennis they play, or just because their presence makes us smile.

This is what a friend is, and the kind of friend we can be to others.

There are good reasons why Zara and Jez struggle to make and maintain friendship today. Forces of busyness, mobility, workplace changes, and neglect work against them – and us. We’ll use Zara and Jez as case studies for the rest of this series, imagining how their stories could progress. For the moment, try listening to your own experience and that of those around you. Do you need more or deeper friendships? What about those in your workplace, university, or other frontlines? What advice would you give to Zara or Jez so far? Start imagining a better future for them, and we’ll see you in part two.

Sheridan Voysey

Author, broadcaster, and founder of Friendshiplab.org

Friendship Lab: evidence-based courses for individuals, churches, and workplaces.

The Lonely Century by Noreena Hertz (Sceptre, 2021): a helpful resource for understanding the socio-cultural causes of loneliness in the western world.

Friends by Robin Dunbar (Abacus, 2022): some resent research on friendship in one book.

Platonic by Marisa Franco (Bluebird, 2022): explores the individual psychological dynamics of friendship.

Friendship by Gilbert Meilaender (University of Notre Dame Press, 1986): a short, helpful study through the lens of theological ethics.

Friendship by Daniel J. Hruschka (California University Press, 2010): a study of friendship across cultures.

[1] Names and identifying details have been changed for privacy.