Wise peacemakers | How to love your culture by triple listening (1/5)

I am sending you out like sheep among wolves. Therefore, be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves. – Matthew 10:16 Wise Doves Being a ‘wise dove’ w...

Read

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

And God said, ‘Let there be light’, and there was light.

God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light ‘day’, and the darkness he called ‘night’. And there was evening, and there was morning – the first day.

– Genesis 1:1–4

What does the Lord want to create through you? What does the Lord want to create in you?

This series of articles is all about becoming ‘wise peacemakers’ who partner in God’s mission through Christ, bringing all of life together under his lordship. Whoever we are, and wherever we’re called to be, we’re invited to work for the flourishing of all things as we love God and our neighbour as ourselves, and cultivate our piece of God’s earth to bring life to the full.

How do we actually do this? That’s the ‘cultural conversation’ we need to have, seeing big ideas and formless hopes take shape right where we are.

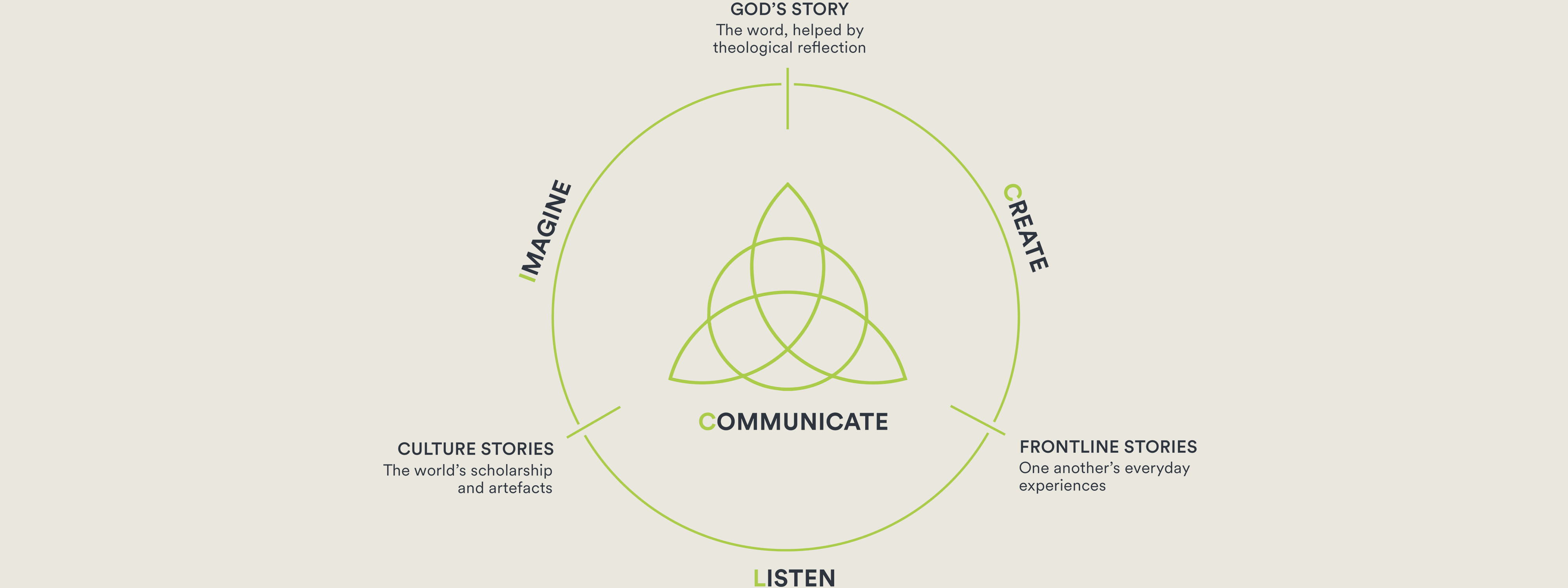

So far, we’ve explored how to listen to our frontline culture, hovering with God over its surface and appreciating its potential and chaos as the context where we’re called to be whole-life disciples. Then, we imagined this place in fresh ways, seeing it through the light of God’s story from creation to consummation by way of the cross, receiving biblical wisdom. In the final article, we’ll discover how to communicate this good news and respond winsomely as we say ‘let there be light!’ to a world weary of religious jargon.

But right now, we need to pause and pray, asking God what it means to live out of this better story for the transformation of the world he loves.

You see, it’s not enough to merely think and talk about culture, mapping the ethos of our frontlines and grappling with big issues from a biblical worldview. We also need to create the change we want to see. We may quibble with Karl Marx on many points, but on this he was spot on: ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.’

Our God is a God of action. Right from the Bible’s opening stanza, he’s busy building a cosmos, and embedding the principles of wisdom so we might carry the image of our Creator and work with his purposes in our culture-making projects.

Can you picture in your mind’s eye the master craftsman bringing order out of disorder, making provision for everything that moves to find its place and come fully alive? Can you see the divine artist catalysing joy for the onlooking heavenly hosts and the world below as he lights up the stage to create beauty and reflect his glory? In all things, God is about releasing potential, and entrusting his image-bearers to do likewise – fabricating tools and technology, cultivating agriculture, making art and music, and forming community.[1] In this, we learn to tend and care for our planet and its inhabitants the way that God tends and cares for us (Genesis 2:15; Numbers 6:24–26).

As even the greats like J. R. R. Tolkien recognise – arguably unsurpassed in his dedication to crafting words and worlds – God is the only one who truly creates something from nothing. We are humble sub-creators, ‘little makers’ playing with God’s materials. And yet ‘makers’ we are. Even as fallen, rebellious creatures, the task of creating remains. But first, God must create in us a new heart, the supreme artisan chiselling us to imitate Jesus the maker (2 Corinthians 3:18; Galatians 4:19; Ephesians 5:1; Philippians 1:6).[2]

God’s creative work is both in us and through us. So in this article, we’ll build on our listening and imagining to create a new story, being formed to act faithfully in a way that brings shalom. We begin by forming bespoke spiritual practices that open us up to God’s renewal of our thinking and emotions, sustaining our particular call, wherever we live and learn, work and play, shop and serve. Then, we’ll revisit the six-act framework for godly imagination from Part 3 of this series, considering our posture to the culture around us, and how to be fruitful as we create healing action tailored to our frontlines.

As before, talking through this framework with fellow believers will draw out insights and illuminate applications you’re unlikely to see when reading alone. Italicised questions throughout are an opportunity to reflect and relate what you’re reading to your unique context.

How does your frontline context give you the opportunity to bring order, make provision for life, catalyse joy, create beauty, and release potential? What does it look like, in practice? Why not take some time, right now, to thank God for his work through you.

Create in me a pure heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me.

Do not cast me from your presence or take your Holy Spirit from me.

Restore to me the joy of your salvation and grant me a willing spirit, to sustain me.

– Psalm 51:10–12

Whatever our character, it bleeds through into our creative efforts, at once blessing and cursing the world. And our context also powerfully shapes us to love and hate certain things that often misalign with God’s heart. There’s a good reason that fields of work are often called disciplines. Just like spiritual disciplines, each ‘vocation’ – and every context – forms people in very particular ways. If you’ve ever stalled in peak hour traffic or been squashed in the train on your commute, you’re painfully aware of how when we’re squeezed, who we really are comes out. We are formed and deformed by our vocation, tempted to take on the shape of the culture around us.[3]

Thinking through the lens of the fruit of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22–23), my former work as an academic interacted with my own tendencies to produce patience, faithfulness, and self-control as I footnoted research, prepared for classes, and fielded recurring questions as students gradually learned the ropes. I was even formed to seek goodness in my craft, working according to the requirements of my trade. And yet, the abilities I developed in critical thinking – analysing before speaking and acting – sapped my joy, subdued kindness under the higher priority of accuracy, and ultimately cooled my love by degrees as knowledge puffed up my ego (1 Corinthians 8:1).[4]

Like King David, I needed to keep short accounts with God in the cut and thrust of my daily context, in order to stay in step with the Spirit and practise the way of the kingdom from a place of joy. I needed to become intentional about counterformation to look more like Christ and less like an arrogant nerd. I needed God to renew me with his perspective.

What about you? As we have done in Parts 1 to 3 of this series, choose a frontline and reflect with me. How does the ethos of this place – seen through its priorities, structures, systems, heroes, habits, and stories – form or deform the character of Christ in you? Try working through each flavour of the Spirit’s fruit, noting where you are moving toward or away from God and awareness of his presence in the everyday.

Particularly in those areas of dangerous drift and deformation, it’s wise to form spiritual practices that counteract the culture, and instead cultivate the image of God in us. This will require practical changes in our daily actions, putting off and putting on habits as befits a wise peacemaker (Ephesians 4:22–24; Colossians 2:6–12).

As we unpack in a longer article here, Christian practices may be defined as ‘rich and repetitive actions we do, over time and often together, which engage our senses and imagination, reminding us of God’s presence and aiming us at his kingdom’.[5] They can include classic practices like reciting the Apostles’ Creed and praying the Jesus prayer; inner disciplines like meditation, prayer, fasting, and study; outer disciplines like simplicity, solitude, submission, and service; and corporate disciplines like confession, worship, guidance, and celebration.[6]

Resources abound to form a rhythm of life where we continue to grow on our frontlines, as we’re grafted into the vine (John 15).[7] We’re to be spiritual athletes in training, uniting our head, heart, and hands – our beliefs, our character, and our actions – through meaningful exercises embedded into our everyday routines.

And yet, knowing the specific deformation that comes through the particulars of our context, we need a few bespoke practices to help us stay the course and avoid turning in on ourselves, forgetting God and his call to mission. Frontline practices are actions done in these places that lead us to an awareness of God’s presence, and foster a desire for his kingdom.[8] In doing so, they open us up to God – who renews the way we think and feel – transforming the sort of people we are as we go into our everyday contexts.

If I’m honest, I love this kind of thing. I’ve worked a few different spiritual practices into my day – but as the old adage goes, it’s not the quantity of practices that matter, it’s the quality. The aim isn’t to micro-plan your every waking moment, slotting in prayers every third breath – but rather to deliberately get into the habit of rededicating yourself and your tasks to Christ during your day.

For me, that includes enriching the habitual washing of my glasses to remove smears, while praying that God’s Spirit would expose my vision blurred by selfish interest and instead give me clear lenses to see those I teach as loved by him. Excessive screen time numbs my body and soul, so I set a one-hour timer during my work day, after which I find a quiet place away from public view, kneel, and lift up particular people on my prayer list. The day closes with a prayer of Examen, signing the cross over my forehead, eyes, mouth, ears, heart, left, and right hand. I pray in turn that God would be glorified through what I think, see, say, hear, desire, write, and in where I went.

Each habit helps me remember who I am in Christ and what I’m called to do in love. Alongside these frontline practices, I pray a prayer about my vocation as a teaching academic, which helps me dedicate my work and self to God each day:

‘Today, my God, I profess that you alone are wise.

Father of lights, illumine my thinking; Son of love, guide my giving; Spirit of life, animate my speaking;

That knowledge of you would ground knowledge of your creation; and

That humility, patience, wisdom, and courage would define my way in the world.

For all that is true, good and beautiful, comes from Your being, and returns to You.

To the glory of the Father, through the Son, by the Holy Spirit.

Now and forever, ad saecular saeculorum, Amen.’

Can I encourage you to take ten minutes today to reflect on how your frontline context forms and deforms you? Then, think of one simple spiritual practice you can commit to on your frontline, accompanied by a vocational prayer if you’d find that helpful, to sustain your everyday call.

‘Wake up, sleeper, rise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you.’

Be very careful, then, how you live—not as unwise but as wise,

making the most of every opportunity, because the days are evil.

– Ephesians 5:14–16

So, God is at work in us, and we can partner in this transformational process. But what of God’s creative work through us? How can we stay in step with the Spirit and make the most of every opportunity, seeing signs of God’s kingdom coming on our patch of God’s earth? For that, we need to retrace our steps in Part 3 on the journey toward shalom, putting into action our framework for godly imagination as we make culture on our frontline.

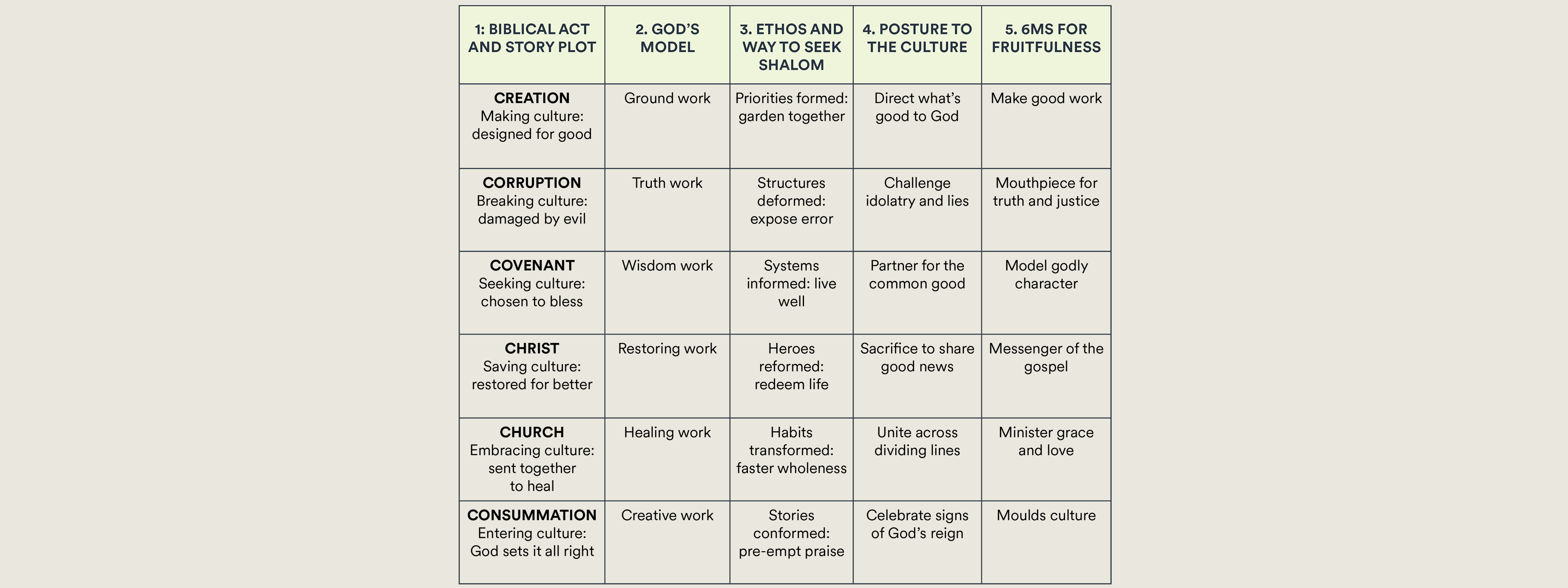

As we reimagined our context through each lens in the table’s first column – creation, corruption, covenant, Christ, church, and consummation – we got a picture of how God was at work and how we were invited to join in (column 2). In turn, as we attended to the ethos of God’s kingdom (column 3), an aching tension – let’s call it a ‘kingdom gap’ – opened up between the core beliefs, values, and guiding purposes of the culture on our frontlines and the beliefs, values, and purposes of Christ and his life-giving culture.

In this gap between what is and what will be when everything is conformed to the will of God, we’re called to be signs of the kingdom – models of a new way to be human. Never controlling or forcing our preferences on others, we are to prayerfully seek wisdom from God, in conversation with other disciples, for how to leverage the power we have to show that a different world is possible, inviting others to join in.[9]

Given that our frontline context is complex, we can’t adopt a single posture to the culture (column 4).[10] Instead, we’re called to be wise in how we live, redeeming the time in these confusing and dark days. Aligned with LICC’s 6Ms of Fruitfulness, we’re to be strategic in how we bear fruit on our diverse frontlines (column 5), letting our light shine before others so they may see our good deeds and glorify our heavenly father (Matthew 5:16).

Remember, Jesus would have us be ‘as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves’ (Matthew 10:16). But this isn’t generic righteousness. It’s tailored to your place, emerging naturally from all you discovered in the listening and imagining you did earlier in this series.

This will take some prayerful work to flesh this out for your particular frontline.[11] To help prompt your own reflections, let me share how the framework above applied to my first job as a high school teacher.

Seen through the lens of creation (column 1), as a teacher I was called to direct what’s good to God by making good work (columns 4 and 5). My primary strategy was simply to keep growing as a teacher, practising excellence in education by creating engaging and transformational lessons, bringing understanding to complex subjects, and caring for each student’s progress, needs, and holistic development. I also offered whatever support and encouragement I could to my fellow teachers so that they would thrive. By doing this, I earned their respect, keeping first priorities first. It also made my gospel words more plausible when presented with the opportunity to point people to Jesus.

Seen through the lens of corruption, I was called to challenge idolatry and lies by being a mouthpiece for truth and justice. As explored in Part 3, my school’s structures formed a hidden curriculum that considered the athletically and academically gifted as more important than regular achievers. When double standards emerged and we played favourites, I asked tough questions and called for rules that were equitable for all. Confessing my own failures was key.

Seen through the lens of the covenant, I was called to partner for the common good by modelling godly character. A heavy teaching workload combined with responsibilities coordinating the curriculum meant that I felt rushed and was at times impatient with both colleagues and students. Through prayer, I was convicted of pride in being able to do it all myself, and instead needed to ask for help in planning units. We rejigged our systems, making space for fellow teachers to brainstorm together at the start of semester as part of our preparation process, swapping resources. I also took on one extra playground duty to help out other thinly spread teachers, play my part, and make space to rebuild relationships in a less formal setting with students I’d unfairly reprimanded.

Seen through the lens of Christ, I was called to sacrifice to share good news by being a messenger of the gospel. We’ll press into how to communicate our faith in Part 5 of this series. Still, in my teaching context, I recognised that my eagerness to evangelise was seen as overbearing and inappropriate by some students and teachers. I re-evaluated how and when I shared my faith, and made space in some of our lunch programmes to invite other perspectives on the big questions of life, rather than controlling the platform. As a result of sacrificing some of my power, following Christ’s model as the humble hero of our faith, more genuine dialogue opened up that matched Jesus’s own free offer of life to the full. A consistent witness of sacrificial love gave weight to my words.

Seen through the lens of the church, I was called to help strangers and enemies unite across dividing lines by ministering grace and love. There were pretty serious tensions in the school community between different ethnic groups. Working with local churches and community groups, partnering with a range of faith-based and secular charities, we were able to offer a breakfast club where those with the greatest needs – often enemies who rarely interacted – were able to help prepare food and serve each other, building a community that was a foretaste of God’s banquet through this simple weekly habit.

And, finally, seen through the lens of the consummation, I was called to celebrate signs of God’s reign by moulding culture. Many of these kids felt beaten down by life and unsafe in their own families, lacking hope for a better tomorrow. They were desperate for encouragement. So, a few of us adopted the strategy each week of noticing one student who surprised us with their creativity, changing the way they did things to practically love their neighbour. Then, we each took the time on Friday afternoon before heading home to call their family, and tell a story of how we saw truth, goodness, and beauty through their teen’s life. On one occasion, the parent of a troubled adolescent didn’t seem to grasp that their child did something good for a change. ‘You call me as soon as they step out of line, and I’ll deal with it’, the dad threatened. It seemed like a fail. And yet, come Monday, this student who caused terror to many a teacher raced up to me, beaming: ‘I don’t know what you said on the phone, but my parents have never treated me so good! Can you call them next Friday, too?’

Simple actions. Nothing profound. But in each of these ways, I could humbly join with Christ, the master craftsman, and create change suited to my particular cultural context.

Work back through these six postures for your frontline. How might God be calling you to create change through strategic action, becoming more fruitful right where you are?

Whoever we are, whatever we do, we’re called to be ‘redemptive changemakers’ who can imagine new possibilities on our distinctive frontlines, and create strategies that function as kingdom seeds.[12] In due time, watered by God, these humble efforts may blossom and bear fruit that blesses many. Again, the strategic action emerges from prayerfully dwelling in the dissatisfaction of the gap between the status quo and the kingdom ethos (Romans 8:18–27). When combined with a vision of what is possible in the Spirit’s dynamic power, and concrete first steps, we can overcome resistance to change and be godly culture-makers.[13]

But this takes wisdom. It’s a slow and prayerful process, best practised in community with other followers of Jesus who share your particular frontline. That way you can fully fit your action to the context, creating a clear plan moving forward. As dry as this sounds, the simplest way to ensure you’ll move from big ideas and diffuse hopes to actually making a difference is to set yourself a SMART goal [14]:

Why not take a few minutes to form one SMART goal now, based on your reflections about your frontline?

Joining God’s work on your frontline isn’t just about strategizing in advance, though. You’ll be faced by challenges in the moment – and we’re all called to respond in a Christlike way, right there and then (in fact, this is often when we find out just how much God has renewed our thoughts and emotions!). While our six-act framework for godly imagination (in the table above) is a great tool to work through in depth over time, it’s a bit too complex to do on the fly. So, when you need wisdom in the heat of the moment, try out this transferable tool.

Put simply, we’re called to water, weed, and weave.[15] How would Christ have you…

Gone are the simplistic gestures of condemning, critiquing, copying, or mindlessly consuming whatever is the culture on our frontlines. Instead, we are called to the posture of gardeners who keep well what’s already there, and artists who make something new that changes the horizons of what we think is possible and how we live in the everyday.[16]

Watering reminds us of the good God created as he formed a purposeful universe out of chaos. On your frontline, right now, there are things to affirm, celebrate, and support.

Weeding reminds us of the cultural idolatry we all participate in as our loves become disordered and we turn in on ourselves, damaging our relationship with God, our neighbours, nature, and ourselves. However pleasant your place may be, you’ll need courage to expose and challenge injustice, at times fighting and other times fleeing the forces of darkness, so that people may be set free.

And weaving reminds us of our call to partner with our Saviour in healing action, because he has good plans to make all things new, starting right now. So don’t be discouraged. Persist in the pain, bearing up under mistreatment, treating the sick, and binding up the brokehhearted. There are signs of life already emerging if you have eyes to see, which Christ longs to fulfil if you’ll walk and work with him.

Spend a few minutes in silence with the Lord. What’s one way he would have you water, weed, and weave, in your everyday mission as Christ’s ambassador?

They will be called oaks of righteousness,

a planting of the Lord for the display of his splendour.

They will rebuild the ancient ruins and restore the places long devastated;

they will renew the ruined cities that have been devastated for generations.

– Isaiah 61:3b–4

We’ve listened and imagined, and now we’re positioned to create with our Creator as wise peacemakers right where we are.

God is at work in us. As we experiment with spiritual practices, may God renew us, as we become a holy community of character who gracefully reflect his perspective. Whilst we’ve mentioned several practices above, a good place to start is a simple breathing prayer, silently repeating short prayers or lines of Scripture to infuse our thoughts with godly truths.

And God is at work through us. As we water, weed, and weave in the Spirit’s power, may we live to see the ancient ruins rebuilt so that all flourishes and those devastated by sin find a home.

We’re called to be culture-makers, participating with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in repairing the ruins of humanity’s fall into sin. For redemption is ‘as big as creation, and as far as the curse is found’.

In Part 5, we’ll finish this series by exploring how to communicate the good news of the gospel in a way that emerges from our process of listening, imagining, and creating, and makes sense to those who are tired of the church speaking Christianese. Until then, God bless as you seek wisdom for the way, celebrating as God’s word continues to take on flesh and illuminate your corner of the world (John 1:9).

—

Dave Benson

Culture & Discipleship Director, LICC

[1] John Dyer, From the Garden to the City: The Redeeming and Corrupting Power of Technology (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2011), 96.

[2] As Dyer explores in his From the Garden to the City (p. 164 onwards, also p235 note 2 for chapter 9 on Restoration), the description of Jesus as a ‘carpenter’ by trade (tektōn, in the Greek) hides this word’s more expansive meaning, from which we derive technology in the English. It is essentially an artisan or craftsman, that is, a maker. God incarnate is thus a ‘technologist and transformer’. Tektōn includes carpenters, woodworkers, builders, ironworkers, even architects. Given the historic period, and proximity of Nazareth to the much larger city of Sepphoris – where the chief building material was stone – it’s likely that Jesus was skilled as a stone-mason. Translated into Latin, tektōn becomes faber, where homo faber means ‘skilled man’ or ‘making person’. As those called to image our Creator God and imitate our Saviour, this is our identity and vocation also: making shalom.

[3] R. Paul Stevens and Alvin Ung, Taking Your Soul to Work: Overcoming the Nine Deadly Sins of the Workplace (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2010).

[4] See ‘Education between Tree, Tower, and Temple: How the Knowledge Project (De)Forms Us’, in Pub Thelogy: Where Potato Wedges and a Beer are a Eucharistic Experience, ed. Irene Alexander and Charles Ringma (Manchester: Piquant Editions, 2021), 139–150, available online at bit.ly/TreeTowerTemple.

[5] See ‘A Litany of Practices’, Practical Theology (2019), with many examples here.

[6] Richard J. Foster, Streams of Living Water: Celebrating the Great Traditions of Christian Faith (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2019).

[7] There are many online tools to keep you plugged into God in the everyday, including these three great apps: Lectio 365; Centering Prayer; and Reimagining the Examen.

[8] For a helpful guide toward this end, see Denise Daniels and Shannon Vandewarker, Working in the Presence of God: Spiritual Practices for Everyday Work (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2019). See my approach here.

[9] For example, LICC’s Executive Toolbox course encourages those in workplace management to change culture through this four-step process: (1) map the story of the status quo; (2) consider kingdom beliefs, purposes, and Christ-like values to affirm; (3) discern the distorted beliefs, purposes, and values to challenge; (4) prayerfully leverage the power you have with the opportunity to bridge the gap; that is, take first steps by enhancing kingdom culture toward the ideal vision, and humbly influence the culture where it is clearly broken. This can take place at multiple ‘locations’ (e.g., self, team, function, organisation), pressing on multiple levers (e.g., celebrating, modelling, rewarding, recruiting, training, communicating, building). For a similar strategy in book-length form, see Amy L. Sherman, Kingdom Calling: Vocational Stewardship for the Common Good (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011).

[10] The classic exploration of this variety of postures is from H. Richard Niebuhr, Christ and Culture, expanded 50th anniversary edition (San Francisco, Harper, 2001). For a reframing of this typology, applied to secular schools, see David Benson, ‘Why We Need the World: Musings from the Interface of Theology and Education’, in Pub Thelogy: Where Potato Wedges and a Beer are a Eucharistic Experience, ed. Michael Frost, Darrell Jackson, and David Starling (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2001), 99–127, available online at http://bit.ly/NeedWorld. An especially pertinent UK treatment of similar themes can be found in Paul S. Williams, Exiles on Mission: How Christians Can Thrive in a Post-Christian World (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2020).

[11] Note that in this digital age, still facing the fall out of a global pandemic, your frontline may also be virtual. See Dave Benson, ‘Being Fruitful on Facebook: Wisdom for the Web’, LICC blog, November 25, 2020.

[12] ‘Redemptive changemakers’ and ‘redemptive design’ come from the work of John Beckett, who heads Seed. They’ve mapped out an excellent design process immersed in the biblical worldview to help Christian entrepreneurs substantially reimagine and rework their context. See seed.org.au/redemptive-design.

[13] In the language of the Beckhard-Harris Change Equation, for systemic change to occur, you must have dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs, a vision of what should be, and concrete first steps charted toward this vision. The multiplication of these factors must exceed resistance to change, or things will stay the same (D x V x FS > R). For more, see Reuben T. Harris and Richard Beckhard, Organizational Transitions: Managing Complex Change (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1987).

[14] See Robert S. Rubin, ‘Will the real SMART goals please stand up,’ The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist 39, no. 4 (2002), 26–27 online here, tracing back to its first use by George T. Doran, ‘There’s a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives,’ Management review 70, no. 11 (1981), 35–36.

[15] For more, see Michael W. Goheen and Craig G. Bartholomew, Living at the Crossroads: An Introduction to Christian Worldview (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 127–145.

[16] Andy Crouch, Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (Downers Grove, Il: IVP Books, 2008), 78–98.

Author

Dave Benson