Wise peacemakers | Imagining on your frontline (3/5)

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.

– Albert Einstein

What does it mean to imagine that a new world is possible? Not a world of your own making, by sheer sweat and ingenuity. But rather to receive from and partner with ‘the God who gives life to the dead and calls into being things that were not’? (Romans 4:17)

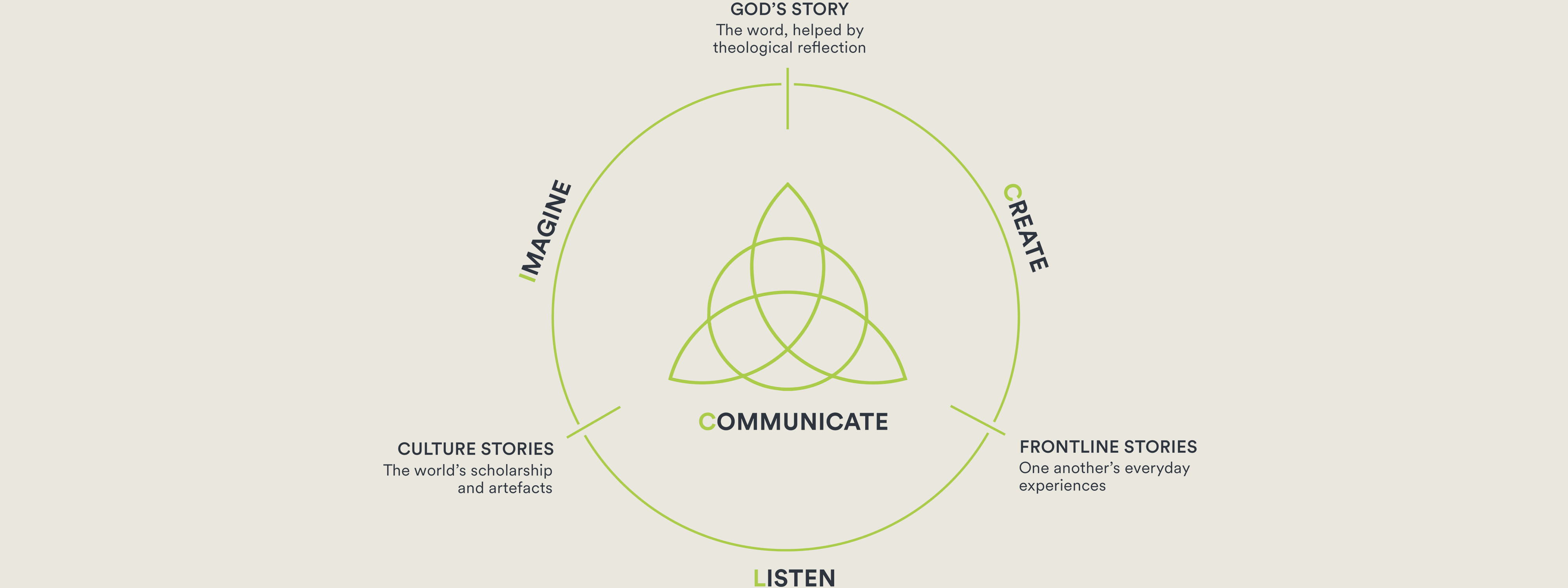

In Part 1 of this article series, we explored what it means to be a ‘wise peacemaker’ right where God has called us to be, and where he is already at work. If we’re to make sense of what’s going on on our frontlines and why, and if we’re to work for shalom in these places, then we need to bend our ear and ‘triple listen’ – to the word of God, the world around us, and one another, as we follow Christ in the everyday.

In Part 2 we began this three-way ‘cultural conversation’ by learning how to listen to what’s going on around us and why, reflecting on the stories we find on our frontlines and in our cultures. We walked the neighbourhood, heard people’s hearts, unearthed the ethos around us (the beliefs, values, and purposes underlying our context), considered cultural artefacts, and located these stories in the wider UK situation. Our knowledge of the places we’re in throughout the week grew in leaps and bounds. (If you haven’t read Parts 1 and 2, you might want to check these out now!)

But we can’t stop at listening. Now it’s time to imagine what should be going on around us as part of God’s big story of mission. Because that’s our focus – imagining with God, so we can join his reviving work on our frontlines.

Figure 1. The Cultural Conversation: The L.I.C.C. Process

Imaging the Son

The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

– Colossians 1:15–17

What do we mean by imagination? Is it fantasizing about some ideal state? Is it a feat of the deluded optimist, a kind of faith in faith itself? Or, like the Mad Hatter, is it a wishful believing in six impossible things before breakfast, if only we can see it in our mind’s eye?

How about, none of the above! In his ‘Auguries of Innocence’, William Blake mused what it would be like ‘to see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour’. To his peers (and more than a few literature students today!), he must have seemed a dreamer. And yet, when we are grounded in God’s revelation and illumined by his light, we can paint poetic, prophetic pictures that point to a new creation – imagining a vision that our peers can barely see. As the dawn comes, and shadowy figures become solid over time, we can retrospectively celebrate with Blake, ‘What is now proved was once only imagined.’

Turning from literature to philosophy, John Stackhouse helpfully unpacks the role of imagination – alongside intuition and reason – in how we perceive the truth and truly know.[1] Imagination takes our best attempts at looking and listening, our jumbled sensory experiences, and enables a sensible ‘reading’ of the world. ‘Imagination arranges these readings into patterns for us to consider.’

For example, in Part 2 of this series I listened to my neighbourhood to discern where God was at work. But what precisely was God doing in these data points? How does what I heard fit with his plans to remake my frontline in the fullness of time? Should I be overwhelmed, or excited, at these possibilities?

Imagination rallies these elements of my experience together so I can understand what’s going on around me, and find a way forward. It positions me within a story where the fragmented pieces fit. And it inspires a vision to mould the culture of my place in line with God’s good plans for his creation. For ‘we cannot consider as a possibility what doesn’t occur to us to imagine in the first place’.[2] Without a clear picture, we literally cannot see and therefore do not move.

When we imagine what it might look like to mould the culture around us, inspired and empowered by our Creator, by grace we’re enabled to speak out what doesn’t yet exist, making a path toward shalom for those around us. We re-see our lives through the light that shines in the darkness, ‘the true light that gives light to everyone’ in the world (John 1:9). That is, we reimagine all that is as held together in Christ.

This makes sense, because Jesus himself is the image of our invisible God, helping us imagine, picture, see, and handle, the one whom we can hardly conceive (Colossians 1:15–29; 1 John 1:1–4). In fact, imagination doesn’t start with our minds at all, but rather with God, from whom we receive biblical wisdom for our frontline situations. We need to make space to cultivate this baptized imagination in order to paint pictures of the kingdom on a drab canvas – in places where we’re tempted to believe God is absent.

Wandering towards a better story…

We’ve considered a literary and philosophical angle on imagination, and soon we’ll get started on this imaginative process for ourselves. But one last consideration – what does theology have to say about imagination?

In Part 1, I suggested that Jesus’s journey to Emmaus with Cleopas and his friend (Luke 24) was a powerful example of what ‘cultural conversation’ and triple listening (to the word, the world, and one another) look like. On the trip, Jesus wakes his companions from their slumber in the dark, reframing all they thought they knew. It’s a story that deserves retelling.

Picture this, then, in your mind’s eye. Jesus has risen from the dead, but his followers didn’t get the message. So two of them leave the bloody city for rural backwaters, heads hung low. Was it all for nothing?

But this stranger pulls alongside, asking ‘why the long face?’. They explain how the man they thought was the Christ – the Saviour of the Jews anointed to liberate them from Roman rule – was killed, and the mission fell apart. Strange rumours of resurrection circulate, but they feel hopeless on their dusty frontline, because they can’t imagine anything beyond what’s presently in front of them, stuck within a small, inherited story of national restoration.

Suddenly this stranger opens their eyes. He says everything in the Scriptures pointed to this moment – a Saviour who frees every single person across all of history, by suffering on our behalf, and conquering a bigger enemy than the current empire. A Saviour who defeats death itself. Jesus walks them back through the whole Bible, ‘explaining from all the Scriptures the things concerning himself’ (Luke 24:27).[3]

Don’t you wish you were there that day? What did Jesus say?

Most theologians suggest that Jesus wouldn’t have simply revealed where he was in particular passages – ‘look, I’m hiding behind the burning bush!’ Rather, he helped them reimagine the whole mission of God, centred on his identity and call as Saviour.

As missiologist Lesslie Newbigin explained, ‘The way we understand human life depends on what conception we have of the human story. What is the real story of which my life story is part?’[4] By relocating their confusing place in first century Palestine within the biblical story from creation to consummation – centred on Jesus’ mission to save the world that climaxes at the cross – they are restored, given a new story, and set on a new path towards Christlikeness. They receive godly wisdom to see their reality through God’s eyes.

Through this same process, we today can be activated for mission right where we are.[5]

A framework for godly imagination

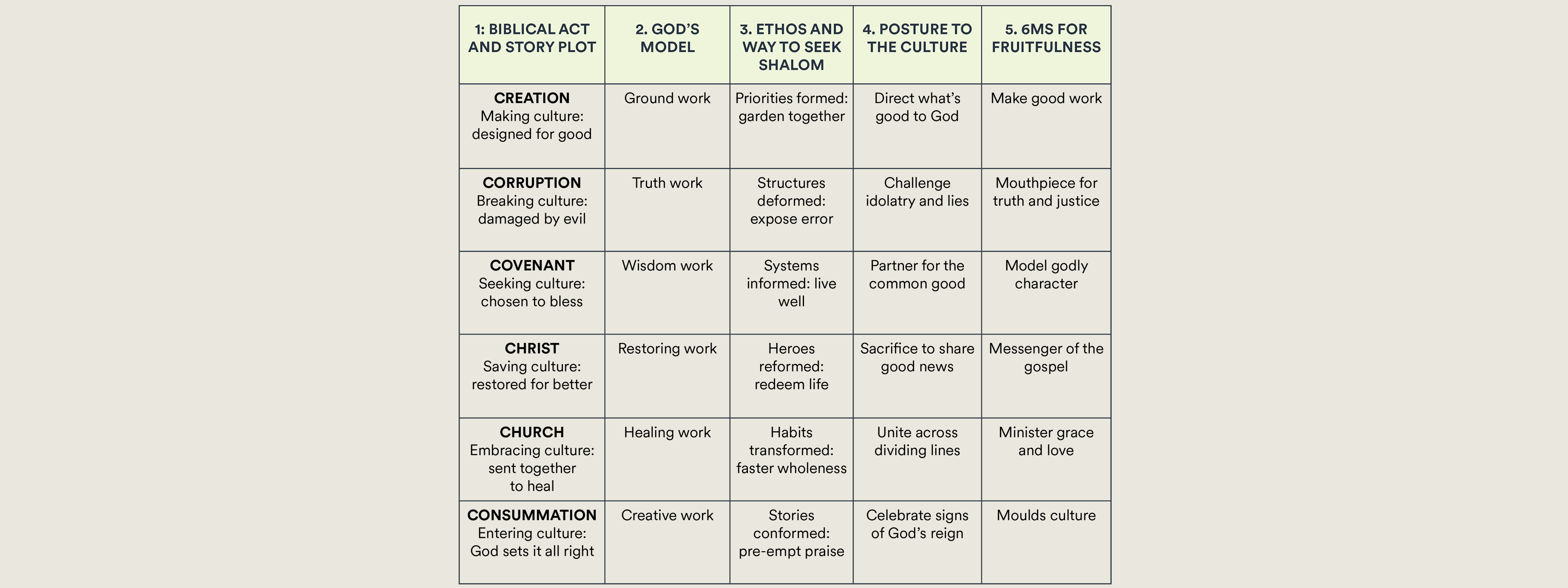

In what follows, we’ll use a detailed framework to help us imagine our frontlines through God’s eyes, as we join him in ‘culture making’ there.[6]

Across the biblical story, each act (column 1) weaves in and out of the others, holding ongoing relevance for how we make sense of our frontlines. We need to read our context through each lens, making connections between what these biblical stories meant to their original audiences, and – through Christ – what God’s mission means to our particular time and place. In other words, we’re retelling the biblical story where we are, imagining what our frontline contexts could look like as part of God’s mission.

As we work through these six acts of the Bible, we’ll see God’s model of work (column 2), which we’re invited to join, and reflect on the six cultural markers of ethos (column 3 – see more detail in Part 2 of this series) on our journey toward shalom. In doing so, let’s pray that God empowers us to picture our frontline in life-giving ways.

Then, we’ll get to the last two columns in this table in the fourth and fifth articles in this series, discovering how to bring healing through a renewed posture towards our culture, and how to respond on our frontlines in fruitful, practical ways.

For now, to illustrate what all this looks like in practice, let’s walk through the six acts of the Bible and consider how they inspire us to imagine our frontlines through God’s eyes. As we go, I’ll share some personal reflections from a former workplace – when I was a PE and science teacher in a secular state school.

1) Creation

Creation[7] is the story of making culture. God designed everything for good, cultivating a garden of delight aimed at shalom – that is, the responsibility and joy of right relationship with God, neighbour, nature, and self. In the process, God models ground work: building foundations for life. The world is formed with the priority of enabling everything and everyone to flourish and work together in harmony.

We’re invited to join in with this ground work on our frontlines as we ‘garden together’ – understanding our colleagues’ priorities, respecting their contribution as fellow image-bearers, whatever their faith or none, and looking for how what they do in the everyday is grounded in and completed by God’s good purposes.

As a teacher, I was laying the ground work for growing bodies and minds. In various ways, through our subject matter and extracurricular activities, my colleagues and I were gardening together: giving feedback; offering praise; helping students learn what would set them up for health and career for years to come.

This is all good, but it’s not the whole story – because you can’t know the whole story without knowing God, receiving his wisdom, and seeing his purposes for the work you’re doing. I was called to work alongside fellow teachers who didn’t know Jesus – and so I was called to direct their work of making a living towards the God who made our bodies and gave us life. I was called not just to help students grow healthy bodies, but also to help them grow as complete human beings, pointing them towards God.

Asking the right questions and revealing God as Creator helps teachers and students alike explore what makes for a life worth living. Of course, every profession – especially teaching in a secular school – limits what you can say and do. But this image of education for life, not just training athletes to win a contest, served to orientate my everyday efforts, keeping first priorities first.

Imagine your frontline through this lens. How might you join God’s ground work, gardening together to form priorities that make for a culture aimed at shalom?

2) Corruption

Corruption is the story of breaking culture. The original goodness of creation remains, but because of our dis-orientation, everything has been damaged by evil. Turning inwards to play God, our best efforts tend to fracture shalom. In the process of addressing our selfish fall, God models truth work: welcoming honesty and justice. The world is deformed in its very structures, harming relationship with our creator, our peers, the earth we were tasked with cultivating, and even defacing our own self-image. We’re invited to join on our frontlines as we ‘expose error’ – not judging, but revealing where things have gone awry and calling for integrity in its place.

As a teacher, I could see how the excessive focus on examinations and an overburdened curriculum was unduly pressuring young people to perform. It came at the cost of wonder at God’s good world and discovering their distinctive gifts. By asking some challenging questions as to how our approach was harming kids, leading them to despise school, we could begin to take small steps to reset the imbalance – building communities of care in our classrooms, and refusing to push students at breaking point.

The truth was, they ‘performed’ better when they loved what they learned. Asking how every subject helped us grow in love of our neighbour and this good planet was a stepping stone to revealing the gaping hole at the heart of education, which only their Creator could fill. Still, challenging these deformed structures helped us imagine a better way to teach.

Imagine your frontline through this lens. How might you join God’s truth work, exposing the error of deformed structures that break your culture and fracture life?

3) Covenant

Covenant is the story of seeking culture – like Israel seeking the promised land, needing godly principles to flourish. God chooses Abraham’s family, and us as his descendents by faith, to bless the world, calling everyone back to their original mandate of loving God and neighbour as they cultivate the planet. In the process, God models wisdom work: showing us how to walk in life’s patterns. We need to study the way God made the cosmos to be, receiving biblical insights to inform systems where everything thrives as each aspect plays its part. We’re invited to join on our frontlines by valuing whatever is true, good, and beautiful – irrespective of its source – so that together we might ‘live well’, following ways that work.

As a teacher, it was obvious how every subject area offered wisdom to live well. Physical education formed healthy bodies, and science gave the knowledge and skills to see how nature worked. But, disconnected from other subjects – like history’s insights into humanity’s failures, geography’s appreciation of how mastery over the planet can destroy ecosystems, and citizenship’s emphasis on the need for people to work together for a greater good – it tended to produce egocentric athletes and proud technicians who couldn’t put life together to know what it means.

Seeing my work through this image of culture making with God, we were able to utilise ‘rich tasks’ that aligned across subject areas, integrating what students learned and encouraging a humble mindset orientated towards something more than their personal performance. They were encouraged to share insights with each other, and educators across disciplines learned to teach together.

Imagine your frontline through this lens. How might you join God’s wisdom work, blessing others as you inform systems in line with his character, learning to live well?

4) Christ

Christ is the story of saving culture. Jesus as God-in-the-flesh brings the story to a climax. He restores us by outloving evil, so we can realign with God’s purposes – the new humanity helping everything flourish, as we were supposed to in Eden. In the process, God models restoring work: leading the lost to freedom and bringing the dead to life. He radically reforms our image of what makes for a hero, as an exemplary individual whose righteous way we’re called to imitate. We’re invited to join in on our frontlines as we too ‘redeem life’ – giving up selfish agendas and trading our comfort so the people around us feel heaven come near and hear good news.

As a teacher, every awards night I could shift the picture of the model athlete. Rather than exclusively attending to the most powerful individuals, we began praising team members who laid down their own comfort and glory, picking up the towel to serve others so everyone might ‘win’. This became a kind of gospel parable, making for opportunities to point to the kingdom. Similarly, each day I prayed for opportunities to give some of my time and energy in helping fellow teachers with lesson plans and learning experiences, offering to cover a playground duty slot once a week, to model the upside-down way of the kingdom.

Imagine your frontline through this lens. How might you join God’s restoring work, embodying the gospel?

5) Church

Church is the story of embracing culture. The community of the forgiven is filled with the Spirit, as they’re sent together to heal a broken world. In the process, God models healing work: binding community back together. Where once we found security in sameness and protecting our own, now our habits are transformed to seek unity in diversity, where everyone’s distinctive gifts are valued and used for peace. We’re invited to join in on our frontlines as we ‘foster wholeness’ – binding up the wounds of the hurt and brokenhearted, and building a friendly family out of strangers and former enemies.

As a teacher, this meant making a habit of noticing points of division, or people who felt left out. I was called to be a peacemaker, so helping to mediate between students who hated each other was a must. It meant listening to both sides and encouraging small steps toward reconciliation. Simple stuff, really: offering a kind word after class, or lunchtime tuition to show I cared. Seeing my fellow teachers as people God loves, rather than units of production tasked with implementing a faceless curriculum. A morning breakfast club, supporting poorer families, became like communion as they gave and received around the table – parents, teachers, and students enjoying one conversation. Hearing each other’s stories, you could see this rag-tag bunch becoming a community, walking together toward new life.

Imagine your frontline through this lens. How might you join God’s healing work, transforming habits to foster wholeness as strangers and enemies become a family?

6) Consummation

Consummation is the story of finally entering kingdom culture, where ‘the way we do things around here’ truly is heaven on earth. The dead are raised, the unrepentant are judged, and the cosmos is resurrected as the Creator sets everything right. In the process, God models creative work: crafting a new world.

No-one can fully imagine the glory of what will be, but in the new creation all our stories will find a fitting resolution, conformed to the will of God for the flourishing of all things. However, we’re invited in the present to join in on our frontlines as we ‘pre-empt praise’ – receiving a biblical picture of what will be so we can look for and craft signs in our messy ‘now’ of a vibrant ‘not yet’ that one day will glorify Jesus – who makes this do-over possible.

As a teacher, this meant asking for divine inspiration in my lesson planning, drawing out the wonder from science students as they found themselves imitating red blood cells, carrying packages of oxygen to rejuvenate distant limbs in a larger-than-life circulatory system. Reimagining my work within this story, I was on the look out for what was true, good, pleasing, and perfect, to praise God’s creativity in his image-bearers. I delighted in their culture making with excellent lab experiments, unbelievable sports strategy, chuckle-inducing fancy dress days, and enjoyment of our school’s entry in the music competition.

Imagine your frontline through this lens. How might you join God’s creative work, telling hopeful stories that pre-empt the praise to come when everything is made new?

Expanding our theological vision

Our journey of triple listening to the word, the world, and one another is well underway. We’ve closely attended to the stories on our frontline, seeing them as part of a wider cultural story shaping ‘the way we do things around here’. And in this article, we’ve imagined our distinctive calling within the mission of God. What a privilege to join his work in the world, and work with Jesus, the image of God and true light giving light to all, as darkness gives way to dawn!

Throughout this post, I’ve asked you to imagine your frontline through the biblical lens. What do you see? To what is Christ calling you? But this is a team effort. Our work of cultural renewal will only ever rise to the level of our theological vision[8] – and that’s formed when we gather as church around the word, inspired by the Spirit to see afresh what God’s doing around and through us. A practice that can help us grow in this is lectio divina, where we come to the Scriptures to receive wisdom for what God’s big story of salvation could look like on our frontlines.

Next, in Part 4, we’ll return to our frontlines, seeing what all of this means as we create change through healing action, sustained by spiritual practices to remember our calling every day. In the meantime, there’s much to be gained by grabbing a friend, or signing up your small group, to work back through this process together.

May what you now imagine be one day proved. God bless as you seek wisdom for the way, playing your particular part as a creative peacemaker in this epic story.

Dave Benson

Director of Culture & Discipleship

LICC

[1] John G. Stackhouse, Jr., Need to Know: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 131–134.

[2] Stackhouse, Need to Know, 133. He continues, ‘The cultivation of a bold imagination that is both free and equipped to wander widely while also remaining in productive contact with the matter at hand is a crucial desideratum of serious thought. … only a vividly imagined alternative will have any chance of affecting our outlook and behaviour.’

[3] For helpful books to understand this sweeping narrative of the Bible, see: Antony Billington with Margaret Killingray and Helen Parry, Whole Life Whole Bible (Abingdon, UK: The Bible Reading Fellowship, 2012); Craig G. Bartholomew and Michael W. Goheen, The True Story of the Whole World: Finding Your Place in the Biblical Drama (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2020); and Roshan Allpress and Andrew Shamy, The Insect and the Buffalo: How the Story of the Bible Changes Everything (Auckland, NZ: Venn Foundation, 2020).

[4] Lesslie Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1986), 15.

[5] James K. A. Smith’s work on this is particularly important, tying desire, imagination, and story together as one in the life of whole-life disciples. See his 2019 LICC talk here, and his books: Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2013), 124–125; You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Publishing, 2016), 89–92; and On the Road with Saint Augustine: A Real-World Spirituality for Restless Hearts (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2019), 158–176.

[6] Many sources are woven together in this framework, emerging out of my doctoral work. See David Benson, ‘Schools, Scripture and Secularisation: A Christian Theological Argument for the Incorporation of Sacred Texts within Australian Public Education’ (PhD dissertation, The University of Queensland: School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry, St. Lucia, Qld, 2016), Chapter 5. It also integrates LICC’s 6Ms, and my address ‘One Caller, Many Callings’ from the 2016 Malyon College Transforming Work conference, further unpacked in Modules 2 and 3 of the ‘Integrating Faith and Work’ course.

[7] In this article, space only permits a sketch of each of the six acts of the biblical story (creation, corruption, covenant, Christ, church, and consummation). A fuller telling of this whole-life gospel can be found by clicking the hyperlinks at the start of each section, taking you to our Lent 2021 Word for the Week series.

[8] See Tim Keller, Center Church: Doing Balanced Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012), 13–26.

Author

Dave Benson