Wise peacemakers | Listening on your frontline (2/5)

Blessed are the peacemakers,

for they will be called children of God.

– Matthew 5:9

When everyone seems so polarised, what does it take to be a wise peacemaker? How do we become whole-life disciples who understand our cultural moment, desiring and working for shalom on our frontlines, Monday to Sunday, as the scattered church?

These questions drive this foundational long-form series in Culture and Discipleship. In Part 1, I wrote about noticing that the seemingly ‘no place’ locations in which we go about our mundane routines are actually ‘God’s house’. Our everyday life is the arena to bless our neighbours, wherever we are! But blessing our neighbours there requires us to practise ‘triple listening’ – slowing down to reflect and listen to the word (God’s story), the world (culture’s stories), and one another (our own frontline stories).

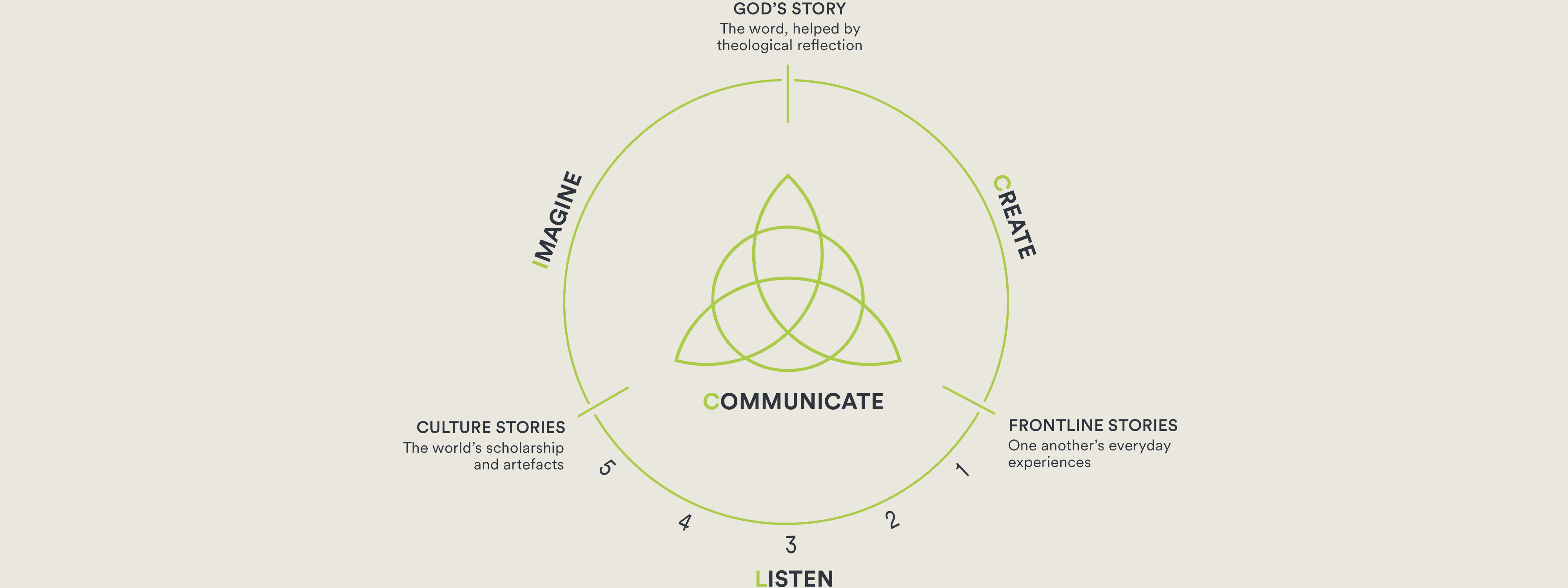

To listen, imagine, create, and communicate in the presence of our triune God is what I’ve called ‘the cultural conversation’. If you haven’t read Part 1, you might want to go explore the big picture before we dive into the topic of listening – which, in our overall framework, sits in the section connecting our own stories to the story of the wider culture, and our world. If you already have, let’s dive in.

Figure 1. The Cultural Conversation: The LICC Process

Let’s consider how to truly listen and reflect on what’s going on and why in our confusing times. I’d suggest there are five steps to listening – building on one another as we expand our attention from our local experiences to the cries and hopes of our society as a whole.

Step 1: Walk the neighbourhood

I am no scientist. I explore the neighborhood. An infant who has just learned to hold up his head has a frank and forthright way of gazing about him in bewilderment. He hasn’t the faintest clue where he is, and he aims to find out. …view the landscape, to discover at least where it is that we have been so startlingly set down, if we can’t learn why.

– Annie Dillard, ‘Pilgrim at Tinker Creek’

Start by picturing one of your frontlines – a place you spend a lot of your time with people who aren’t following Jesus. I’m thinking of my apartment complex where we just moved, but you might choose your work or gym. Try to keep thinking of it as you read through this article and each of the steps. What does it take to listen well, so we might be wise peacemakers in this particular culture?

Your frontline is not an empty space. This is God’s place, though we knew it not. We can see how God’s at work and learn from our neighbours at the same time. So, unplug those noise-cancelling headphones, and get walking! What do you hear? What do you see?

Wander and wonder with your heavenly Dad, as he shows you around. Rock up early and stay a few minutes late at the places you frequent. Pray for the flourishing of this frontline (Jeremiah 29:7). What a difference it makes to see this site as a portal where heaven meets earth, the stage where God’s plans to bless take place!

So look around, a bit like Paul exploring Athens’ marketplace in Acts 17. Whether at work or where you live and play, ask yourself: ‘what is beautiful and praiseworthy here? In what do people on this frontline take pride and find joy? How have they ordered this space to function better?’ See your community in this place less as a machine and more as a giant body with organically interconnected bits. Like platelets in the blood stream, where do people flow, gather, even clot? What rituals, routines, and rules shape the way they do things? Conversely, what seems strange or distorted? Where have things become run down, and what – or whom – do they overlook or talk down? See what God points out. I jot my observations in an online journal, reviewing them every so often to see what’s changed.

For me, doing this has meant slowing down and chatting in a covid-safe way with neighbours. Noticing that one couple leaves before the sun’s up. Discovering they’re shift workers for National Rail, but love a quiet countryside walk and occasional banter about their favourite takeaway. They’re kid-free, but playful at heart.

It’s not about focused inquiry. It is about a posture of prayerfully paying attention. It’s about discovering that this place is actually God’s house. What is going on around here, and where is Jesus already at work? Where might I be called to join in or speak out? Listening as you wander is where your frontline mission starts.

Step 2: Hear people’s hearts

‘It is the essence of wisdom to be a discerning, discriminating listener and to choose carefully whom to listen to. … To take the time to listen to God and to our fellow human beings begins as a mark of courtesy and respect, continues as the means to mutual understanding and deepening relationships, and above all is an authentic token of Christian humility and love.’

– John Stott

Now, like Jesus on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:15), draw near and ask some questions. What tales do your neighbours tell, making meaning out of everyday experiences? Where is the drama? Scan the ‘news’ features on your work’s bulletin board, your town’s Facebook group, the paper they read. This isn’t muckraking, gleaning gossip. Simply listen to the tensions and resolutions characterising their everyday experiences and personal stories.

Some of us might be tempted to ask big ‘worldview’ questions or discuss global problems to find out what makes our neighbours tick. Where did we come from? Who are we? Why are we here? How should we live, and where are we going? What’s our problem, and how do we solve it? But everyday issues can reveal just as much. They’re the tip of an existential iceberg. Ask what people are interested in, and you’ll see God under the surface.

Neighbours aren’t projects or problems to fix. They’re people God loves. So hear their hearts. The Holy Spirit may already be drawing them; don’t butt in on this conversation. Listen! Just getting my hair cut, I got to know a young man who’d recently moved here from Turkey. He loves his job but is desperately lonely and unsure how to make friends. I could sense Jesus’ love for him, so I listened while he snipped away, and lifted him up in prayer. God willing, with another trim or two, we’ll move from acquaintances to mates.

Trust is built over time, through multiple conversations in a range of contexts. Work may cross over with a social event, chats over coffee, and eventually a home meal. It’s invasive to ask directly – but instead we can be prayerfully attentive to six key areas of people’s lives:

Life – when are you really switched on and what makes you happy?

Pain – what disappointments do you carry and where do you hurt?

Wisdom – where do you go for guidance and whose voice do you hear?

Support – where do you belong and to whom do you turn for help?

Purpose –what wounds in the world do you most want to heal?

Destiny – what’s your picture of the good life and for what do you hope?

We should listen not to proselytise but simply to understand and love people on our frontlines wherever they’re at. Even so, each question is a window into why the gospel is good news for them, right in their particular situation and moment, which may naturally come up when a bridge is built.

Psychologising is out. This isn’t social chess, positioning yourself for a gospel checkmate. Instead, seek to truly hear your neighbour, delving beneath the details to desire: what do they passionately love and genuinely hate? Who are they? Taking the time to listen is a way of honouring them as a fellow image-bearer. Simply and patiently care and connect.

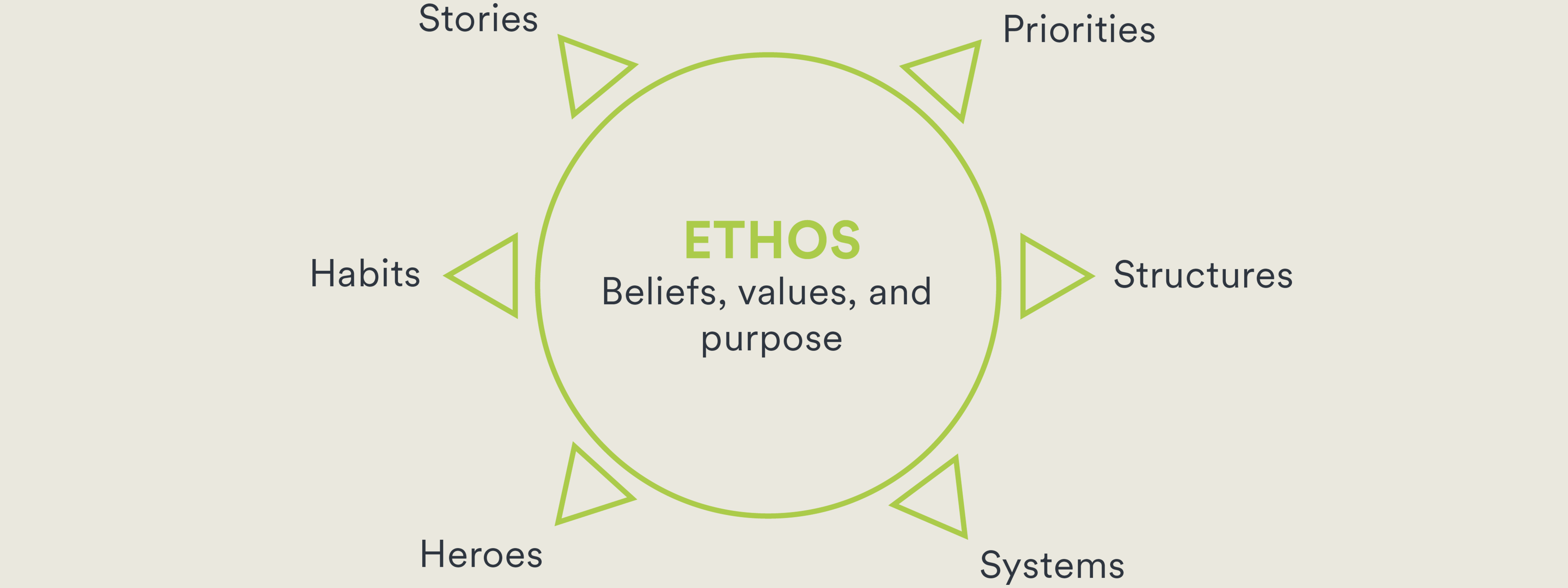

Step 3: Unearth the ethos

Time to delve under the surface, and look at the ethos of the place you are in.

‘Ethos’ is the heart of your culture. It’s the fusion of core beliefs, values, and purposes that energise your community, explaining the way we do things around here. But, it’s not the kind of thing you can directly see. Instead, we need to look at how it is manifested in everyday life, through tangible ‘culture’. It’s an expression of how we imagine the world we’re in, the observable marks of how we see and move in our context.

Just by taking the first two listening steps explained above you are positioned to love, helping you better connect your faith with people on your frontline. But there’s so much more to be gained if you keep going, and look at the whole context! The next three steps are more involved and best worked out in conversation with fellow Christians who also know and love the place you’re in, so it’s not just your individual view of it. Together you can start to reflect together on your everyday experiences, on what’s going on around you and within you. In doing so, you’ll begin to examine the ethos of a particular context, how it shapes and is shaped by those who are in it, and what is says about the people in that place – including you. Once you understand the ethos, you can start to identify what it’s shaping – and how to shape it. That’s powerful stuff.

But how do we get at this underlying ethos? How do we reflect on what we find on our frontlines? Just like how we know about the sun by experiencing its warmth, and seeing by its light – even when we can’t (and shouldn’t!) stare directly at it – we can learn about the unseen ethos of a place by questioning and examining the cultural markers we experience. The ethos of a context affects its priorities, structures, and systems; it directs who we choose as heroes, working its way out in particular habits we praise, all wrapped up together in the stories we tell – and listen to.

Asking these questions about your frontline culture will illuminate and unearth why we do things a particular way in our distinctive place.

Figure 2. Mark Greene’s reframing of Culture as ‘Ethos’

- Priorities – what is the highest priority and measure of success on this frontline?

- Structures – what structures help this group of people hang together as a tribe, and what roles and responsibilities does each member have so it functions in a healthy way?

- Systems – thinking of this frontline as a living body, what systems ensure everything works as it should, with key processes directing energy to get things done?

- Heroes – who do we celebrate as heroes? How is their life praiseworthy from the perspective of this culture?

- Habits – what habits do we reward and reinforce, or punish to discourage?

- Stories – what stories do we tell to capture the vision of what should be going on around here? Listen, also, for what goes unsaid. Silence shapes culture too.

Let me demonstrate using my time and place – in my apartment complex again, just as we in the UK were working to come out of our third lockdown in May 2021. It’s clear through conversation that the ethos in my apartment complex is shaped by the wider UK context. In general, the priority is vaccination so we can get back to ‘normal’ life – work and socialising. We’re bound together by structures like WhatsApp groups, Zoom calls, and regular news updates. Transport and health systems are trying to work together with local GPs so we can ‘jab and go’, with the most vulnerable protected first. In the first lockdown, we were encouraged every Thursday to ‘clap for heroes’, especially NHS workers who embody sacrificial service at its finest. The PM makes announcements on the telly encouraging ‘hands, face, space’, and discouraging selfish habits of illegal gatherings, to slow transmission. Finally, this whole ethos can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery’s ‘Hold Still’ exhibition and the story of Captain Tom Moore completing 100 lengths of his garden before his 100th birthday to raise NHS funds. As these aspects of culture come up in conversation, I can better love who my neighbours are, and make sense of why they speak and act the way they do.

Having observed these six cultural rays, we’re able to discern the core ethos from which they emanate. Essentially, we value the preservation of life and protection from suffering above all else; we believe that by following this costly route now, we can construct a ‘new normal’ for the purpose of freedom and happiness post-pandemic.

Chatting about what we notice like this helps us more deeply understand our context, and better work for the flourishing of right where we are.

Step 4: Consider an artefact

As we just explored, the ethos on our frontlines – the deepest beliefs, values and purposes driving the way we do things around here – is often hidden. There’s a lot of reflection – even an element of prayerful guesswork – required to to make it explicit, and it’s easy to misread motives when we talk about ‘culture’ in the abstract.

So, at this point it’s wise to consider an artefact, like the Apostle Paul did, so he could connect by quoting Athenian poets in Acts 17:28. I’m not talking about something ancient you dig up from the ground. It’s just something – anything – we create that helps us make sense of our confusing life on this planet! It could be something as common as lipstick – an everyday object, but also a cultural window into our vision of beauty and concern for image. Fashion, architecture, smartphones, works of art, poetry, and more each say something about who we are and what we love. When you put them together and pay attention, a picture emerges of why we think we’re here. A story can be constructed of ‘the good life’ toward which we’re drawn. This is gold to help you listen well on your particular frontline.

This step, then, is a way of checking the ethos you unearthed. It helps us reclothe these abstract beliefs and values with flesh. Humans don’t trade primarily in ideas. Rather, our stock is in stories. If we want to know why our frontline culture takes the form it does, it’s helpful to scan the Brit and BAFTA winners for albums and films that show something of how we understand the world, just like we do in our Connecting with Culture articles.

When my family moved from Brisbane to London mid-pandemic, I was given both a box-set of The Crown and the award winning British film Fish Tank. Lest I remain a tourist in my new country, I needed to get into the headspace of both pampered royals at Windsor Castle and an aggressive teen on an Essex estate, walking a mile in their cashmere slippers and Nike trainers. More recently, watching London’s 2021 New Year’s Fireworks was an eye opener into not just British culture but, again, this cultural moment. Each lit drone signalled our self-understanding, together telling a story of facing down a pandemic and rising like a phoenix from the ashes.

This isn’t about having a penchant for high art or being pop-culture savvy. It’s about prayerfully soaking in the songs, movies, novels, and media that resonate with those on your frontline. They’re a window into their soul, often saying clearly what’s on your colleague’s heart, which they can’t or dare not voice. What meaning do they make?

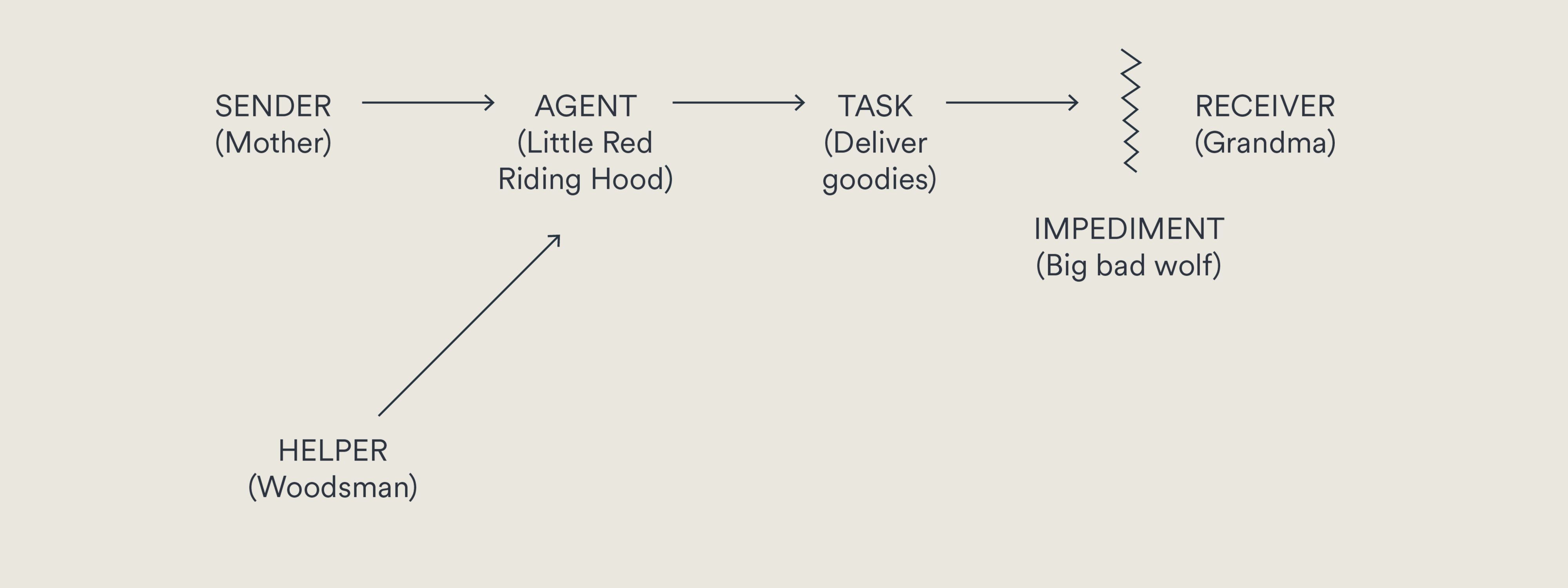

One of the best ways to listen to these stories is by analysing the plot, as in the diagram below, drawing on the story mapping of theologian N. T. Wright.[1] Take Little Red Riding Hood. The mother sends this girl, as the agent in the story, on the task of delivering goodies to her grandma as the receiver. But, the ferocious canine is an impediment, only overcome with the help of the brave lumberjack. Grab any of the most popular stories today – in the news, a movie, a book, an article – and we can also plot each of these categories. When you find a story which resonates with people on your frontline, plotting it is a powerful way of understanding the values they hold, how they see themselves and others, and the way things work in your context, such as dynamics in a workplace.

Figure 3. Categories for plot analysis, illustrated by the tale of Little Red Riding Hood.

For example, when I read Bernadine Evaristo’s Booker Prize winning novel, Girl, Woman, Other, I was transported through twelve searching characters to places British society would never permit me to tread. The characters share a troubled past, hope for the future, longing for a home, and a desperation for a loving touch. Considering Girl, Woman, Other, and listening to its characters, has positioned me to better understand the story of a couple downstairs in my apartment complex.

Here’s how they might see their lives so far. They feel that ‘the cosmos’ put them here to find love and joy by being their authentic selves, which is a gift to the world, just as each of us carves out our own unique path. But their family’s religious fundamentalism was an impediment, causing their family to reject their relationship. It took brave campaigners to change the law so their union was civil. We may see things differently, but that’s the tale they tell.

For the characters in the book, and for my neighbours: who is the sender, and what mission are they on? What enemies block their path? In their tale, is a follower of Jesus a helping friend or dangerous foe?

Considering an artefact like this helps us piece together the stories through which our neighbours make sense of their lives. What stories best speak for those on your frontline?

Step 5: Locate the story

So far, we’ve explained what’s going on by listening closely on our frontlines, reflecting on our experiences to unearth the ethos, and checking our insights by considering artefacts which resonate in this cultural moment. Still, why is this ethos the way it is? I’m still talking about making sense of our own unique frontline, not about the UK in general. The focus is the particulars on our street, in our workplace, in our circle of friends, wherever we are. Starting there is a must. That’s the place where we’re called to be Christ’s hands and feet. But to truly understand what’s going on in these particular places, we do need to locate them within the larger cultural story shaping us all – British culture, the world as it is now in this cultural moment. Wise peacemakers know how to read the signs of the times (Matthew 16:3). And this takes some study.

Through God’s common grace, there’s a lot we can learn from the world’s authorities and experts, in both Christian and secular scholarship. Setting aside a bit of time each day to wrestle with a respected text or podcast, and chat about what you find with others – like we at LICC do in our Open Book gatherings – helps us wisely discern the cultural drivers shaping our communities. If ploughing through a big book isn’t your thing (which is entirely understandable!) ask around and find a solid BBC documentary or radio programme on the topic you’re exploring. Any time you put into becoming more informed is well spent, just like Joseph and Daniel trying hard to get into the head space of Egyptian and Babylonian culture. Studying their language and texts equips you to better understand and serve the people with whom you live, learn, work, and play.

Whatever issues affect your frontline, why not dive a little deeper? If your frontline is the office and everyone there seems to be focused on making loads of money and blowing it on weekends and holidays, with no thought for the above and beyond, then find a friend and together explore How (Not) to Be Secular by philosopher Jamie Smith, or listen to ‘This Cultural Moment’ podcast with Mark Sayers and John Mark Comer. If your vegan friends are increasingly angry at our mindless addiction to consumption, try reading Beyond the Modern Age by economist and theologian Bob Goudzwaard and Craig Bartholomew, and snack on some roasted chickpeas while watching ‘Our Planet’ with David Attenborough!

While not everyone learns best by reading (although I promise these are more approachable than they may sound!), there are workshops like LICC’s ‘Wisdom Labs’ to attend, TED talks to watch, and conversations to join. As for which sources to draw from, it’s important to remember that we’re all finite and fallen, limited and biased, so Christian authors don’t get a hall pass to say what they like without scrutiny. And scholars beyond the church shouldn’t automatically get quarantined as impure. We need to listen well to God’s revealed word wisely read (Acts 17:11) to help us test whether what we’re hearing from others is good and true. No need to be scared – just be wise. Read, test, and examine everything in community. As Christian scholar and journalist John G. Stackhouse, Jr., explains in his book, Need to Know, as we learn and grow together, we can trust God to give us what we need to know to do what we’re called to do.

The point is, be curious, search widely and well, and really study – it’s worth it. When you see the lifestyles, the habits, the loves, the hates, and the concerns of those on your frontline, dig in and gain deep understanding. This all sows into listening and loving well.

What next?

Now we’ve started our journey of ‘triple listening’. Again, take a look at your own frontline – the one you’ve been thinking of. Why not try these steps on this frontline, starting this weekend?

Walk the neighbourhood, prayerfully paying attention to where God is already at work. Choose a few people on that frontline and hear their heart as you care and connect. Unearth the ethos, reflecting on what you hear to better understand the context expressing their deepest values, loves, and hates. Ask for a recommendation and consider an artefact voicing their desires and beliefs. And make some time to study the best of relevant scholarship to locate their story in this larger cultural moment.

And if you want to grow in your ability to listen and reflect prayerfully on what’s going on and why on your frontline, why not try the prayer of Examen. It’s a practice that will help you slow down, consider what God might want you to notice from your day, and become the sort of person who listens well.

In Part 3, we’ll shift from listening to what is going on and why, to imagining what should be going on as we see our frontline within God’s story of saving the world through Christ.

In the meantime, may God bless as you seek wisdom for the way to shalom, making a difference in your extraordinary time and place.

Dave Benson

Director of Culture & Discipleship

LICC

[1] This graphic reproduces Figure 1 from J. Richard Middleton, ‘A New Heaven and a New Earth: The Case for a Holistic Reading of the Biblical Story of Redemption’, Journal for Christian Theological Research 11 (2006), 78, here. He’s drawing on the story mapping of N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1992), 71–77.

Author

Dave Benson