Rage against the machine | What do we do now? (2/2)

We use our devices every day. But how often do we consider how they use us? What does it mean to live wisely as a disciple in our high-tech age?

In this piece Matt Jolley, part of the Culture & Discipleship team at LICC, thinks about the implications for our everyday lives as we seek to live and share the gospel in relationships and contexts saturated with digital technology.

This two-part series accompanies Wisdom Lab: Rage Against the Machine, in which the author explores this topic further. Wisdom Labs help churches and small groups explore issues facing Christians today.

Setting the scene

To say that technology plays a significant role in our lives is an understatement. When we realise the ways in which our tech is forming us, and understand what it might look like to be formed increasingly into the image of God instead, what then? How can we celebrate technology’s God-given function, but also recognise its failings and limits? And what difference might this make to the way we live, day by day?

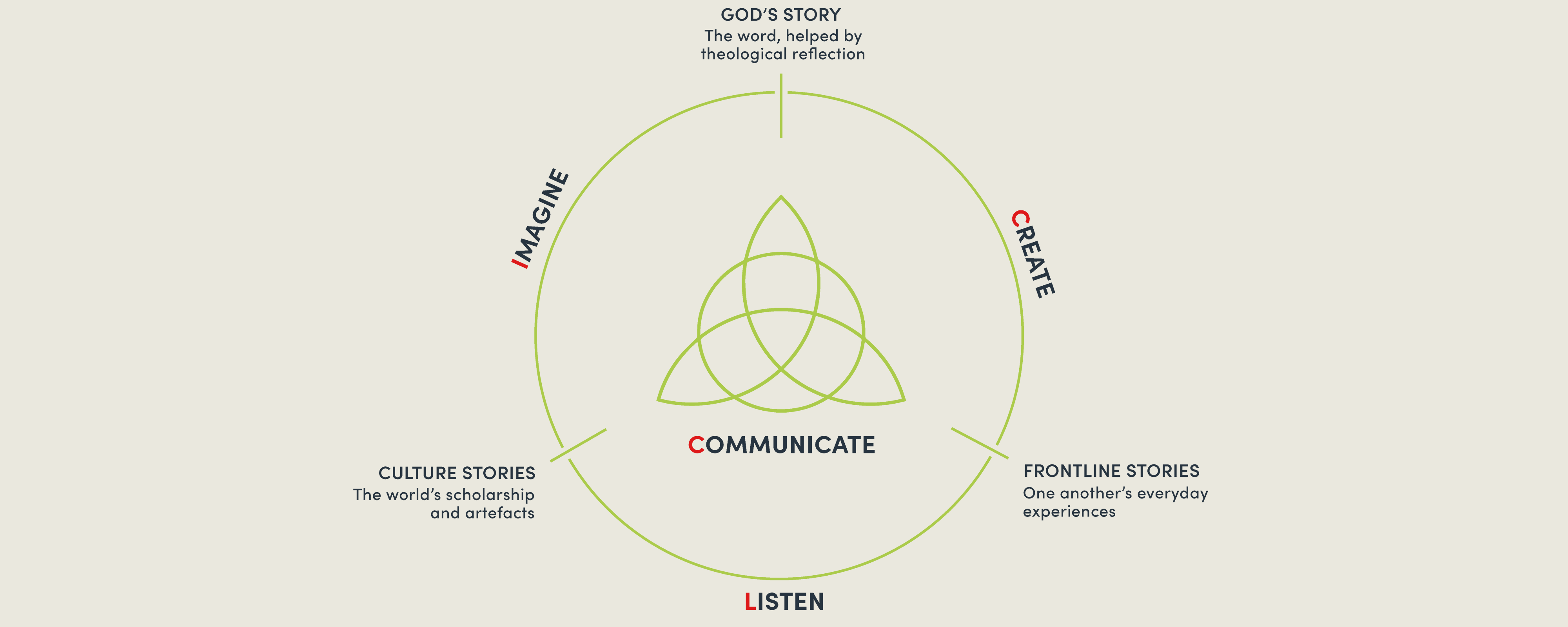

Figure 1: The Cultural Conversation – The L.I.C.C Process

Answering these questions requires triple listening – to the word of God, the world around us, and one another. One way to do that is to use the L.I.C.C. process. We’ve listened to what’s going on in the world of technology, appreciating its many benefits whilst also becoming aware of the effect our devices are having on us. We’ve imagined what the role of technology should look like, put in its proper place in service of God’s mission.

Now, it’s time to get specific as we think about what it looks like to use our devices, and our phones in particular, to serve God’s purposes – as we look to worship him with our whole being. How might we create a set of practices (more on those shortly) which magnify the image of God in us, lead us towards in-person connection, and orientate us towards loving God and loving our neighbour on our frontline? And, lastly, how can we communicate the good news, as a better alternative to the gospel of digital salvation?

The power of practice

Before we flesh out what a response to tech’s influence in our lives might look like, flowing from our habits into our daily lives, it’s worth explaining why we’re talking about ‘habits’ and ‘practices’ at all. After all, wouldn’t it work to just plan out the best way to use technology, and then get on and do it?

The issue is that our tech doesn’t primarily influence us at a ‘head’ level. Even if I believe in the benefits of using social media, that doesn’t mean I’ve been rationally convinced that the best way to live is to spend countless hours scrolling – but that’s what I do nevertheless. When my phone tells me how much I’ve used it each day, I often think it’s too much. When we read tragic statistics around the way that increased phone use leads to lower mental health, we know it’s not good. But what we think isn’t the main issue – that’s not how an addiction works.

Instead, it’s our hearts that matter, which are formed by and expressed through our habits. We know we shouldn’t spend hours every day on our phones, but we want to, because we desire that dopamine hit that comes from seeing the notification light up, and we like the ease and convenience that our devices afford us.

Actually, much of our technology use comes from habits that are so ingrained we don’t think about them at all. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been out walking and my natural reflex has been to reach for my phone, even if there’s nothing specific I need to do. Or when I get home from work, my instinct is to flop down on the sofa and browse through social media. Our habits are powerful things which shape our hearts – and technological companies play on this fact to appeal to our addiction.

So, the answer to the question ‘how do I use technology in a more godly way?’ often isn’t just ‘think better’ – though of course we use our brains to consider the best use of technology – but ‘act differently’. And that starts with rebooting our habits.

Through repeatedly using our technology in a different way, we form new habits, which shape us not as consumers but as image-bearers captivated by God, worshipfully partnering with him in his mission to save the world and make all things new. Let’s unpack that in more detail.

Create – how might we respond?

As all culture is created good yet fallen, the values of our tech will often overlap with godliness in some places and violate it in others. That means the way we use it may not look like total acceptance, or flat-out rejection, but a nuanced approach which maximises the good and restrains the bad.

Often, though, we’re not the best judge of this – my wife is certainly quicker to notice when I’m looking at my phone during conversations than I am! So we also need a community around us, reflecting together, giving accountability for any changes that are needed.

What does that look like, in concrete actions? In a moment we’ll get specific and look at some apps you might find on your phone as case studies. But first, a word on the types of action we can take to form godly tech habits.

Andy Crouch helpfully distinguishes between ‘nudges’ and ‘disciplines’. Nudges are changes that we can make to the environment around us, which don’t force us to do anything but help us make the choices we want. Imagine water flowing down a hill: it’ll choose the path of least resistance. By making changes to the scenery, digging troughs or dykes, we can make it easier for the water to go where we want. These nudges work in a similar way – rather than being channelled towards what our tech wants, we can help lead ourselves towards what God wants.

For example, when I have dinner with friends, I want to give them my undivided attention. But I know that if my phone is in my eyeline – and especially if I can see the screen, with each notification screaming ‘pick me up’ – I’ll focus less on them and more on my phone. If I put my phone in the other room instead, so it’s out of sight and out of mind, I’m able to be more present.

Similarly, I’ve installed time limits on the apps I overuse. Of course, I can choose to use the app anyway by turning the limit off, but that choice is made a bit more difficult and deliberate.

How might you shape the space around you to reform your tech choices?

At the same time, nudges won’t always be enough. We can’t totally control our environment, and we’ll regularly be faced with the choice of whether to align ourselves with our technology’s values, or with biblical values. It’s here that we need ‘discipline’, or what the philosopher of technology Albert Borgmann calls ‘moral courage’: the willingness to suffer temporary discomfort or inconvenience for the sake of what’s right. This sort of courage is made especially difficult by the fact that our tech tells us to prioritise comfort and convenience, but the more we make this choice, the easier it gets.

Think of the water again: even where we don’t manipulate the landscape, flowing water creates a channel, which deepens over time, meaning that this channel gets easier to find. That’s the power of habit: when we continually choose to prioritise biblical values, the choice gradually gets easier to make. We’re re-habituated as the new humanity.

For example, when I’m meeting a friend and my phone flashes up with a notification, I choose not to reach over, but instead return my attention to the person in front of me. Or, when I’m looking to relax, I can choose to read a book that will engage my mind, rather than passively consuming media that doesn’t. Spiritual practices like fasting, abstinence, and silence can also help. When we repeat these practices, we intentionally put ourselves in a place of inconvenience. In the process, we’re training ourselves to grow in ‘the willingness to suffer temporary discomfort for the sake of what’s right’.

Specific app-lication

Let’s consider what nudges and discipline might look like when applied to a few different applications on our phones. To do that, we’ll return to the idea we covered in part 1: that God made us to be relational, creative, and to work, and that our tech use should support those aims.

Firstly, we should aim to use our phones in a way that’s relational. This means bonding with real people, ideally in person, through meaningful conversation, in order to develop strong, caring fellowship.

Think about your social media apps. They facilitate differing levels of engagement, from absent-minded scrolling to commenting to messaging to calling to arranging in-person meetings. The start of that list is more indirect, passive, and less relational. The latter part builds towards what we seek – direct embodied connection.

On Facebook, that might mean limiting our use to keeping up with people we actually know, rather than the long list of ‘friends’ that we don’t, and choosing to be hospitable rather than judgmental in comment threads. On Twitter, it might mean becoming aware of the algorithms that push us towards echo chambers, instead intentionally seeking to engage with a diverse virtual community.

On WhatsApp, it might mean refusing to treat messaging as an adequate substitute for in-person communication. And when meeting someone in the flesh, it might mean putting your phone away (or – horror! – turning it off), to be fully present, instead of being ‘alone together’.

Secondly, we should aim to use our phones in a way that’s creative. This means looking to acquire skills, engaging with our call to be culture makers.

On Instagram, that might mean using your posts to showcase the beauty of God’s world and work, and experience godly awe through other posts, rather than endlessly scrolling through self-promotional selfies and product ads. It means turning outwards to celebrate others rather than gazing inwards in comparison, and authentically documenting the life we have (if we feel the need to document anything at all) rather than the life we want others to believe we’re living.

Thirdly, we should aim to use our phones in a way that supports meaningful work, reflecting Adam’s call in Genesis to tend the garden of Eden. During work hours, that might mean resisting the urge to pick up your device and distract yourself – if like me you’re one of the 70% of people who keep their phone ‘within eye contact’ at work, perhaps it’s time to give ourselves a nudge, put the phone away, and make it easier to focus.

It might mean trying to meet colleagues in-person where possible, to encourage greater creativity and to connect in a deeper way. It might also mean using your phone at work in a way that serves God’s mission, perhaps organising your home screen so it points you towards apps that boost productivity rather than those which distract you. Or, maybe set a wallpaper image that reminds you, every time you open your phone, that God is passionately involved in your work.

Working well also means resting well, embracing the limitations that our technology sometimes wants us to forget. Perhaps limiting the time you spend at home looking at work emails on your phone would help that work-rest balance.

Or, you could try a technological Sabbath, and use it as an organising principle (an hour per day, a day per week, a week per year away from your devices). This can provide a vital reset, contributing to a sustainable way of life that pushes back against the lie that we need to be connected 24/7. (For more on this, join our next Open Book discussion series on The Common Rule). It also helps draw a line between rest and escapism. When we use technology in our downtime – anyone else battling a mild Netflix and YouTube addiction? – chances are we’re actually distracting ourselves from proper rest. Where we do use streaming apps, which encourage passive consumption so strongly, it might mean curating what we watch to ensure the content is engaging our imagination and leading us to wonder.

And with our phones in general, it might mean limiting screen time much more than we already do. So often the more I use my phone each day, the more I tend away from active engagement and direct communication towards distraction and pure consumption.

Limiting screen time is especially important when it comes to sleep. A simple but effective nudge is to put your phone away an hour before bed, out of your bedroom, and leave it there til the morning. I’m much less likely to give in to that desire to check my phone in bed when it means getting up and walking across the house, and I’ll sleep a lot better for the lack of blue light before lights out. And to top it off, the less we’re on our devices, the more we’re likely to be out and about, exercising and caring for our bodies as temples of the Holy Spirit.

Though these are all small steps, added together they’ll eventually have a significant frontline impact. When repeated actions become habits, not only do they get gradually easier but they also affect our heart as we become transformed in response to the gospel. This, in turn, will affect how we act in the day-to-day situations we find ourselves in, including on our frontlines.

When we restrain the desire to look inwards to our own convenience, we are better placed to look to the needs of our neighbours. When we check our screen time, or leave our phone out of sight, we’re better able to be present with the friend in front of us. When we intentionally create a diverse community on our social media, we’re better able to disagree with our family or housemates in a Christlike manner. When we’re in healthy rhythms of work and rest, we can live distinctly in a hurried and exhausted work environment.

When we use technology in a way that magnifies the image of God and serves his purposes, we can demonstrate a different and better story to those around us, living wisely in a technologically saturated world.

Communicate – how can we share good news on and for tech?

To close this mini-series, let’s end by exploring one final aspect of our engagement with technology: if we know what it looks like to live out a different story on and through our devices, then how might we share that story with those around us?

Our tech preaches an alternate gospel, in which convenience is the ultimate good and salvation comes from ever-more sophisticated devices. How can we relate the Christian gospel to those we know who are totally immersed in that narrative?

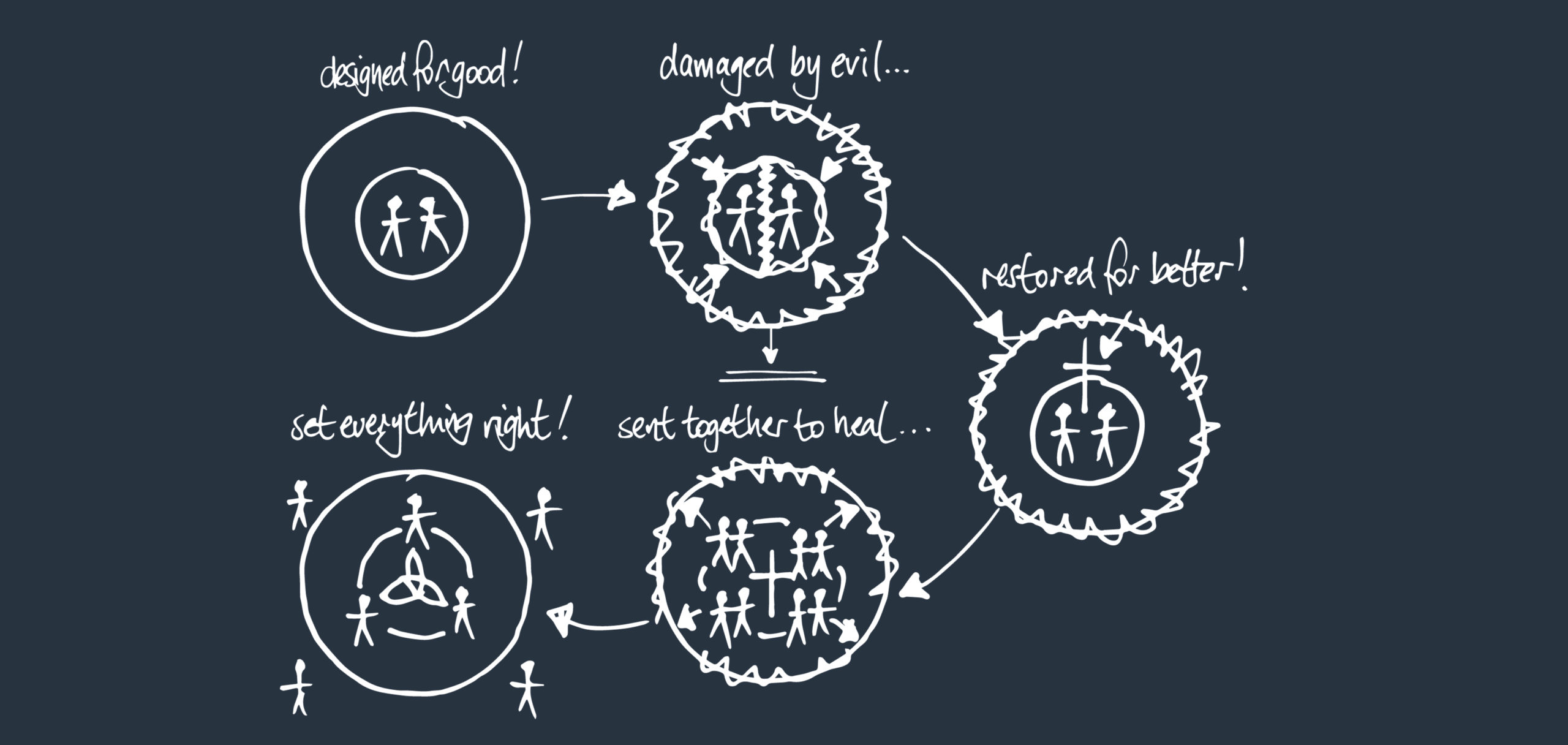

To give you some ideas, this five-circle ‘big story’ lays out a framework within which you can improvise.

Figure 2: The Big Story. Artwork by Deb Mostert (2011).[i]

In the beginning, God crafted the world, and placed humans in the garden. We’re not here by chance but were created with a mission, and technology was designed to contribute to that mission, as we use it to make culture and transform the world around us, taking us from the garden to the garden city.

However, we’re also fallen – damaged by evil – and so turned in on ourselves. Much of our technology has gone the same way, leading us towards its version of the highest good: ease, convenience, and comfort, achieved by ever-increasing efficiency. These things aren’t bad in themselves, but when overemphasised they become idolatrous, as humanity’s desire to find satisfaction apart from God. And ultimately, our accelerating technological advancement implicitly tells us that one day, all of humanity’s problems will be solved by an algorithm, a machine, or an app – that with enough time and research, we can upgrade our way to utopia.

But true though it is that technology brings about a lot of good in our world, that overarching ‘gospel of technology’ misses a crucial point. Because in Christ, we see a victory won not through superior intelligence but through humility and obedience, even up to the point of experiencing death. Repentance and faith in him lead to a moral and spiritual ‘upgrade’ which turns us outwards again, pointing us to love God and neighbour. This is a transformation that affects every area of our lives. We’re restored and renewed for better, joining with a community of love – sent together to heal – to serve God’s mission.

This is a foretaste of the time where everything will be made right. Not through a purely human utopian vision, but through the kingdom of heaven coming in its fulness, where God completes his work. In the garden city, the best of human technological inventions are carried in, giving glory to the Creator of all (Isaiah 60; Revelation 21:24).

Looking forwards

Across these articles, we’ve begun to experiment with the L.I.C.C. framework, applying it to digital technology and particularly our phones.

These two pieces are just the beginning, outlining the nature of our relationship with tech, and its potential role within God’s mission. There are many more ways in which we can live in response, and much more that could be said on how to tell the good news in a technological age. But hopefully this has got you thinking about the changes you can make to re-shape the way you use tech as a disciple on your frontline, partnering with the work God’s already doing there.

To go further, join us on 27 September at our Wisdom Lab, where we’ll discuss together what technology’s place in our lives should be, and how to use it wisely as disciples in the 21st century.

Questions to consider:

- What values would you like to shape the way you use your phone?

- What nudges or disciplines could you use to regulate your phone use in line with those values?

- Which apps do you spend most time on, and how might you use them in a way that better serves God’s purposes?

- Is there someone you could try to communicate the gospel to using the five-circle framework?

- How might technology help/hinder us in sharing the gospel?

TL;DR

- Our response to technological saturation has to involve more than just our intellects. It has to involve our actions and habits, through which we’ll reform our hearts.

- To assess how to best use each piece of technology, we start with the biblical values we want to pursue, then consider the values that are espoused by the technology, before seeing where they overlap and diverge. Then, we’ll be able to discern how to use the tech in a way that maximises the good and restrains the bad.

- Concrete actions can happen in the form of nudges or disciplines. The former are changes we can intentionally make to our environment which make the godly choice easier, and the latter requires the moral courage to choose wisely.

- Our use of our phones, and of specific apps, should aim to turn us outwards towards our neighbour, rather than inwards towards ourselves. When we use our phones in a way that encourages relationship, creativity, and meaningful work, they can help magnify the image of God in us, and lead us to a place of worship.

- The technological worldview in which we’re immersed proclaims its own gospel, with ease as the highest good and human intelligence as our ultimate saviour. But the Christian gospel – from creation and fall to redemption, transformation, and consummation – gives us a better story to tell, not rooted in what we can do but in what God has done, and looking forward to the kingdom only Christ can bring about.

Digging Deeper:

Andy Crouch, The Tech-Wise Family (Baker: Grand Rapids, 2017): Crouch’s ten concrete commitments for putting tech in its proper place are worth noting again.

John Mark Comer, The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry (Hodder & Stoughton: London, 2019): Though Comer’s focus is wider than just technology, the practices he suggests – silence, solitude, Sabbath, fasting – will all serve us well in our relationship with tech.

Justin Whitmel Earley, The Common Rule (IVP Books: Grand Rapids, 2019): another exploration of how to put together ‘daily and weekly practices designed to form us in the love of God and neighbour’.

John Lennox, 2084 (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, 2020): Lennox maps out the technological landscape of today, then traces the goodness of the gospel in the face of our idolatry of all things high-tech.

—

Matt Jolley

Culture and Discipleship – Research & Development

[i] Adapted from the 4-circle diagram found in True Story by James Choung. Copyright (c) 2008 by James Choung. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL, USA. ivpress.com. The 5th circle, ‘Set everything right!’ has been added to the original 4 circles.

Absolutely brilliant very well written, to the point. Insightful in looking at the way technology can be used wisely rather than technology using us.

Thanks Matt Jolley

Truly insightful and truthful addressing of this annoying yet unavoidable issue. Great to have people give opinions and inputs as a genuine discussion. That’s all that is needed for a release of frustration and pain in relation to this issue. Many great points from the speakers and participants. A meaningful and helpful event to be and didn’t want to leave when it was time to close.

Thanks Katherine – it was great to have you join us for the event! I’m glad you enjoyed it, and blessings as you consider how to use your phone in accordance with God’s purposes going forwards!